WITCH HUNT!”

That’s how President Donald Trump’s tweets tend to refer to the investigation led by Robert Mueller into possible collusion between his presidential campaign and Russia.

Except for modern adherents of the Wiccan religion, people today do not believe in witchcraft—and Wiccans do not believe in the sort of witchcraft that became the subject of prosecutions in early modern Europe and America. The consensus among historians now is that witches did not exist in the past, and so by employing the term “witch hunt,” the president is implying that he is as innocent today as were the persecuted “witches” of centuries ago.

He is assuming, probably correctly, that Americans today understand his phrase in exactly that way. Anyone raised or resident in the United States has surely heard of the most famous “witch hunt” in American history, that which occurred in Essex County, Massachusetts, in 1692–93, named for the town in which the trials occurred: Salem. Indeed, many high school students today must read Arthur Miller’s famous 1953 play, The Crucible, which effectively used the vehicle of the Salem trials to comment on the House Un-American Activities Committee investigations of the 1950s, which had ensnared Miller and many of his acquaintances. Even though Miller changed many historical details to make his points—for example, turning the elderly John Proctor into a younger man and the child Abigail Williams into a femme fatale who seduces him—his image of the trials retains its hold on the American imagination.

Therefore, when President Trump or other Americans refer to “witch hunts,” the Salem trials are the point of reference, even though earlier “hunts” in Europe produced many more trials and executions. (An excellent overview of these trials is Robin Briggs’s Witches and Neighbors, now sadly out of print; another good survey is Bryan Levack’s The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe, recently updated in a new edition.)

The scholarship on the Essex County crisis is vast, and interest in the subject appears never-ending. As the author of a well-known book on the crisis, In the Devil’s Snare (2002), I receive many inquiries from students doing National History Day projects on the Salem witchcraft trials each year, regardless of the competition’s official theme. For seven years, concluding this past fall, I taught an undergraduate seminar at Cornell focusing exclusively on Salem witchcraft, which always attracted healthy student enrollment.

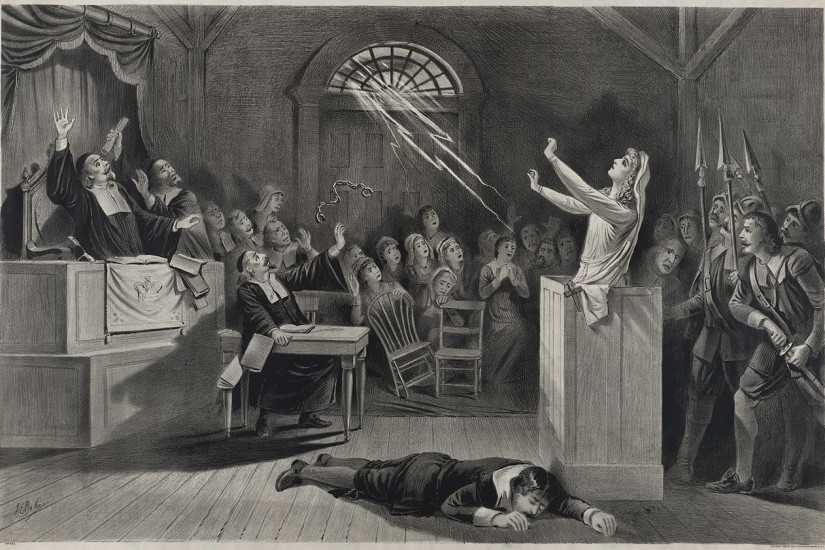

Interest in the trials extends beyond the classroom. Multiple television networks have been sufficiently fascinated by the story to attempt to recreate it visually without any contemporary evidence besides documents that omit many pertinent details. I have appeared as a talking head on numerous such shows, which have varied considerably in quality. I am also one of the scholars interviewed on the video about the trials that is now shown at the National Park Service headquarters in Salem, and which is better than most such efforts. (Among ourselves, historians of Salem refer wryly to the “screaming girls” that dominate many reconstructions.)

Because the trials have drawn attention since shortly after they concluded (the earliest historical treatment came in Daniel Neal’s History of New-England, published in London in 1720), the facts have been overlaid for centuries with layers of myth, some nearly impenetrable. Myths are so much a part of the story that it is almost impossible to reveal the truth. Here I will address just a few.

First is the shorthand name of the event: the Salem witchcraft trials. True, the trials took place in Salem Town, but the crisis began in the outlying area then known as Salem Village (now Danvers). Further, the more than 150 accused people came from all over Essex County, a plurality of them from Andover. So, attentive readers of my book might ask why its subtitle is The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692, rather than my preferred phrase, The Essex County Witchcraft Crisis of 1692. Answer: the tyranny of online search terms. I knew that if I used the more accurate subtitle, some readers (or purchasers) would never find the book.

Second is the story that the crisis began when some young girls became hysterical after practicing some sort of black magic with the African slave Tituba in the household of Samuel Parris, the Salem Village minister. Arthur Miller included a vivid such scene in his play. But there is no contemporary evidence to back up the tale. Tituba obviously interacted with the two children who lived in Parris’s home—the first to be afflicted—but there is no evidence that she associated with the later afflicted young people, most of whom were older teenagers. Nor is there an account of the accusers experimenting with magic together. Even Thomas Brattle, a contemporary critic of the trials who blamed the young accusers, did not suggest that their accusations arose either from Tituba’s influence or practicing witchcraft with one another.

Moreover, scholars now accept that Tituba was Native American, not African. She is always referred to as “Tituba [or some variant spelling] Indian” or “the Indian woman” in surviving records. So why has she been frequently presented as African, or possibly mestizo, including in Maryse Condé’s compelling 1992 novel I, Tituba? The identification of her as African goes back to the 19th century, when no one realized that early New Englanders frequently enslaved Indians as well as Africans. Since she was clearly enslaved, authors thought she had to be at least partly African, despite the repeated references to her as “Indian.”

Historians today do disagree about where she came from: Elaine Breslaw, author of Tituba, Reluctant Witch of Salem (1996), thinks she was born in South America, captured, and transported to Barbados, where Parris acquired her; I concluded that she was most likely captured at the Spanish missions in Florida or the Georgia Sea Islands. Thomas Hutchinson, who in his youth knew people involved in the trials, called her a “Spanish Indian” in a draft of his 1765 History of Massachusetts Bay. And historians now know, thanks to Ann Marie Plane and other scholars, that “Spanish Indian” refers to people captured in raids on Spanish missions—people who might indeed have been sent to Barbados before being brought to New England.

I have neither the time nor the space here to address in detail many other enduring myths, such as: only women were accused and executed (no; 25 percent of the accused and 6 of the 20 executed were men); the only accusers were the “afflicted girls” (no; many witnesses against the “witches” were their neighbors and even some relatives); convictions were based entirely on spectral evidence (no; charges of sickening or killing people or their animals were offered in nearly all the trials); and, finally, the convicted were burned at the stake (hanged, yes; burned, no).

If readers of this column want more information about the truth of the iconic American witch hunt, I refer you to my book, to Emerson Baker’s exemplary A Storm of Witchcraft (2014), or—if you would prefer to consult an accurate edition of the surviving records—to the definitive Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt (2009), edited by Bernard Rosenthal and an international team of scholars.

And a further note to those interested in the replies to the second and third questions in the unscientific survey I first reported last month: you will have to wait until my fall columns. My discussion of the answers to the second question was preempted by . . . witchcraft.