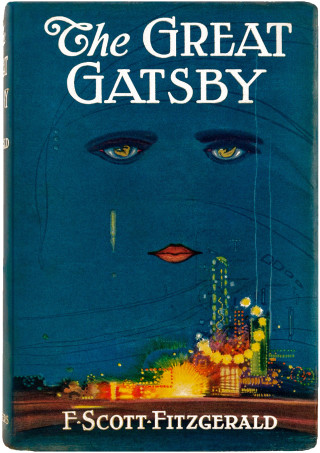

Seen through the dust, darkly, The Great Gatsby reads like an exercise in the waste of energy (coal), land (Flushing Meadows), and life (Myrtle, Gatsby, and George). You can read its famous ending many ways, but one of the most disturbing is that there will be no returning to the “fresh, green breast of the new world” that “flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes.” Like Tom, Daisy, and Jordan, whom Nick will call “a rotten crowd,” the continent, like milk, has soured. Starting with the Dutch sailors, as the land is developed, it is simultaneously despoiled. Ashes cannot turn back into coal. Nor can the dump turn back into the ecologically vital wetlands it used to be.

One of the titles Fitzgerald gave to his novel—he was never satisfied with any of them—was Among the Ash Heaps and Millionaires. The title juxtaposes landscape (ash heaps) and humans (millionaires), and its preposition, Among, implies a shared world, one that includes both setting and character. And so it is. Or was. Until the city turned to its master builder to clean up the mess—a master builder whose reading of The Great Gatsby would inspire him to redeem the wasteland.

If you go looking for the valley of ashes today, you will find not ashes but a baseball stadium (Citi Field), a tennis center (home to the U.S. Open), two man-made lakes, an amusement park, and most disconcerting of all, a stainless-steel sculpture of the globe measuring 115 feet in diameter. There is also a zoo. In less than a decade, the Corona Dump went from blight to blessing. In doing so, it embodied the decisions that would lead, step by step, to our own experiment in creating waste, and to the potentially catastrophic climate change we face as a result.

In 1934, New York City closed the Corona Dump. But now it had a valley of ashes on its hands. Where others saw ashes, Robert Moses, the infamous urban planner, saw an opportunity. In 1932, Moses was appointed Commissioner of the New York City Parks Department, the perch from which he would oversee the remaking of the city for the next twenty-five years. In 1934, Moses added to his resumé when he was appointed chair of the Triborough Bridge Authority and salvaged that project from runaway costs and runaway incompetence. Unsatisfied by his bridges, Moses sought to build a parkway—what eventually became Grand Central Parkway—connecting the Queens–Wards Island span of the Triborough Bridge to the existing parkway of Eastern Long Island. The route, Moses wrote a few years later, “led inevitably along the Flushing Bay through the Flushing Meadow and the middle of the Corona Dump.” “This was the logical place for it,” he added, “but only on the assumption that there was to be a general reclamation of the surrounding area.” In the midst of the Great Depression, however, “there was no sign of money in the offing.”