In this telling of the tale, America’s national parks remain wild and untouched. But that story is too simple. Parks always have been imperfect vehicles for noble protectionism—and few places demonstrate this as well as the Rocky Mountain region of northwestern Montana known today as Glacier National Park. This special place has glaciers, of course, and also rugged peaks, hundreds of lakes, and almost 3,000 miles of streams; it spans more than a million acres and straddles the Continental Divide. For many Americans, Glacier has long represented a wilderness frontier where unadulterated nature reigns.

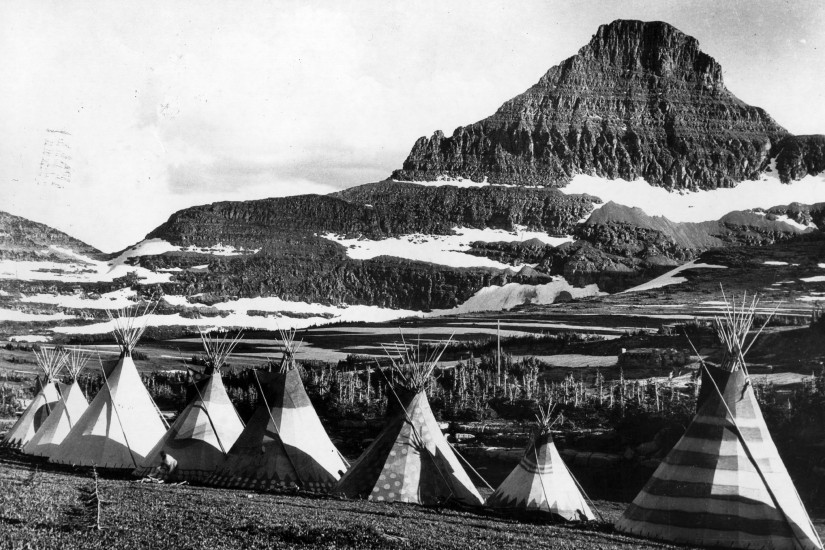

But, in fact, human history and culture permeate Glacier, a place shaped by Native Americans’ dependence on the land, conservationists’ efforts to enshrine its beauty, and corporate America’s exploitation of its treasures. The Blackfeet have for centuries called it the “Backbone of the World,” the source of spiritual power and life forces that animate indigenous life and tradition. The American conservationist George Bird Grinnell dubbed it the “Crown of the Continent” and considered it an ideal place to preserve for national identity and culture. Louis Hill, the president of the Great Northern Railway, sold it as “everybody’s Park,” a symbolic place where Americans might encounter the source of the nation’s greatness. In broad outlines, Glacier’s unnatural natural history is shared by many of the nation’s beloved wilderness parks.

In large part, Glacier owed its establishment to Grinnell, a scientist, writer, and conservationist from New York who first visited northwestern Montana in 1885. Grinnell knew magnificent scenery—he had explored Yellowstone National Park with the U.S. Army in 1875—but Montana’s Rockies awed him. Launching from the state’s St. Mary country, he climbed into the mountains, hunted bighorn sheep and fished trout, met a party of Kootenais traveling from their homeland west of the divide, saw glaciers (including what is now known as Grinnell Glacier), and basked in the colorful “artist’s palette” of the wilderness.

In his writings, Grinnell ignored plain evidence of the human impacts that had been wrought there by native peoples, choosing instead to wax poetic about nature, and nature alone.