While rural boys learned to shoot rifles in the 18th and 19th centuries as part of farm and frontier life, gunmakers drastically expanded production during and after the Civil War, and found that post-war rural and hunting demands couldn’t keep up with supply. The early 20th century saw a concerted effort on the part of the gun industry to nurture a desire for guns in urban and suburban youth. This market didn’t need guns, but gun manufacturers with eyes on their bottom line believed that boys should be taught to want them. At the same time, there was a sense of national “panic,” writes Mechling, over American manhood. He describes the years following the Civil War as “decades marked by economic uncertainty, increased immigration, urbanization, and social Darwinian worries that modern society was feminizing American men.”

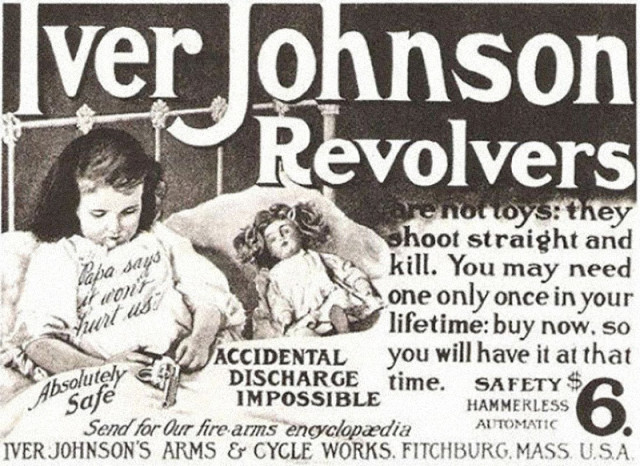

An advertisement for Iver Johnson revolvers via Wikimedia Commons.

The NRA responded to national concerns over the waning of “masculine virtue” by founding its youth programs in 1903, aimed at urban and suburban boys. Soon thereafter, in 1910, the BSA was founded “for the boys who’d paid the price of urban civilization and who were far removed from the wilderness experience that fostered manly virtues like self-reliance and physical fitness,” Mechling continues. The BSA actively distanced itself from being perceived as a paramilitary organization, instead “linking rifle marksmanship to responsible democratic citizenship and to masculine virtues of self-control.” Boys were taught to see guns, not as weapons of war and killing, but as symbols of American patriotism and peacekeeping. (In line with this vision of guns as keepers of the peace—the Colt revolver was known as the “Peacemaker.” “The good people of this world are very far from being satisfied with each other,” Samuel Colt once wrote, “my arms are the best peacemakers.”)

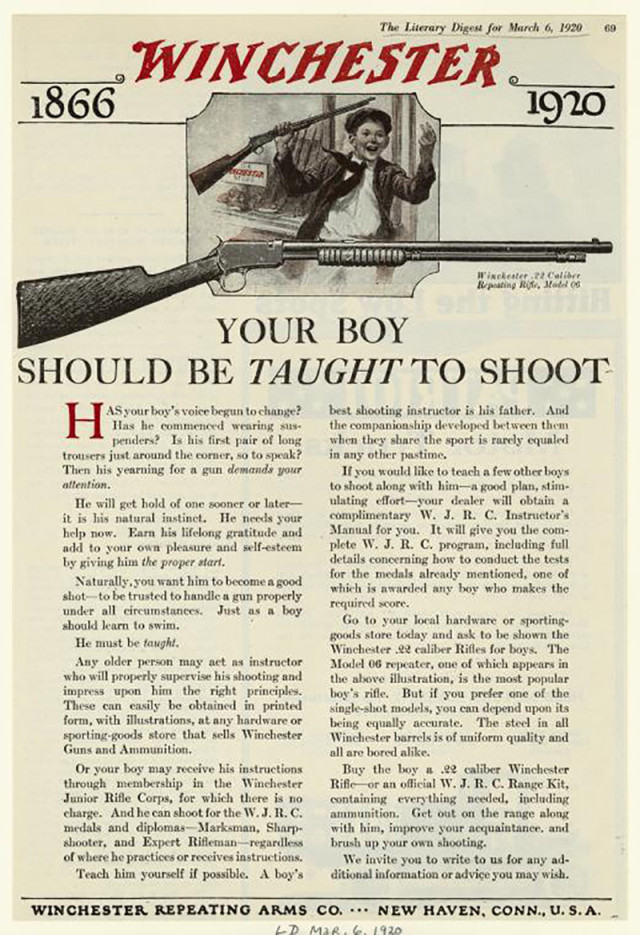

Gunmakers, too, promoted guns as tools for a boy’s character development—not killing. In The Gunning of America, historian Pamela Haag details how The Winchester Repeating Arms Company developed a “boy plan” in 1918, to invite 3,363,537 boys into their Junior Rifle Corps through direct-mail campaigns. Ad slogans decreed that every “real boy” wanted a Winchester rifle to cultivate “sturdy manliness.” When parents resisted—dealers often complained that Mom and Dad weren’t eager customers—“Winchester urged retailers to appeal to the source, not to the parents, and tell their ‘boy customers’ about their rifles,” Haag details. Marketing for the Daisy Air Rifle similarly directly addressed their target consumers: “Tell Dad that you want a Daisy…that you want as much good, clean, fun, and as much chance to be a man, as he had.” Daisy promised children their product “makes you ready for the big gun—the kind Dad uses now.”

A Winchester advertisement from 1920 via Wikimedia Commons.