According to most accounts, America’s opioid crisis dates back to the late 1990s. That’s when predatory Big Pharma companies like Purdue Pharma lied to doctors, falsely claiming that opioid painkillers like Oxycontin and Opana were safe and non-addictive. Prescriptions for addictive opioids skyrocketed during the 2000s, sparking an epidemic of drug addiction that quickly spiraled out of control.

But while this narrative might be convenient, it isn’t the full story, because, devastating though it is, this is not America’s first opioid crisis. Its roots go far deeper. America’s earliest opioid crisis occurred 150 years ago, in the aftermath of the American Civil War, when an epidemic of prescription opioid addiction killed tens of thousands of Army veterans.

Tragically, America’s vintage opioid addiction epidemic shares surprising and disturbing parallels with today’s opioid crisis, calling into question the familiar stories we tell ourselves about how the opioid crisis began and what it will take to solve the epidemic.

Doctors have been prescribing opiate painkillers since the Bronze Age, and by the time the Civil War broke out in 1861, opiates were the most commonly prescribed medicines in America.

During and after America’s bloodiest war, in which 750,000 people were killed with millions of survivors left in chronic pain, Army doctors saw opiate medicines as the most “indispensable drug[s] on the battlefield—important to the surgeon, as gunpowder to the ordinance.” Syringe-wielding surgeons gave morphine injections—cutting-edge technology back then—to dull the unbearable pain stemming from gruesome gunshot wounds and last-ditch, hacksaw amputations.

Doctors doled out opium pills and morphine shots for practically any ailment. Off the battlefield, opium was a surprisingly effective treatment for diarrheal diseases like dysentery, which often hit troops living in squalid conditions.

Doctors doled out opium pills and morphine shots for practically any ailment.

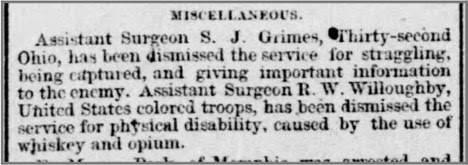

Naturally, thousands of Civil War veterans got addicted to opiates. Like today, most addiction started with prescriptions. Military doctors introduced soldiers to opium and morphine during the war, and sick and injured survivors simply kept on taking the medicines after leaving the Army. Like today, doctors didn’t prescribe opiate painkillers equitably to white and Black soldiers. Some racist doctors believed their Black patients couldn’t feel pain and didn’t need painkillers, while other surgeons took for themselves the painkillers that were meant for injured black soldiers. Consequently, most Civil War veterans who got addicted were white, a product of the shoddy medical care provided for Black troops.

There were no regulations on narcotics during the Civil War era, so the drugs were cheap and easy to get. Opium pills, morphine, and hypodermic needle kits were sold in pharmacies over the counter. You could even order them by mail from Sears. Unsurprisingly, addicted veterans were everywhere in post-Civil War America, and the opioid crisis was covered widely in the press.