Amazon recently received patents for an “ultrasonic bracelet” that tracks workers’ movements. Pitched as a labor-saving device, they monitor how efficiently workers fill orders as well as giving them positive “haptic feedback” -- a little vibration -- as they reach for the correct bins, reducing unnecessary motion.

If this sounds a bit like planning to turn humans into robots, you are not alone; the news prompted a minor hysteria (complete with references to the dystopian science fiction series “Black Mirror”). However frightening, though, it’s hardly new. In fact, several long-dead pioneers of “scientific management” anticipated this development, even if they might not entirely approve of Amazon’s approach.

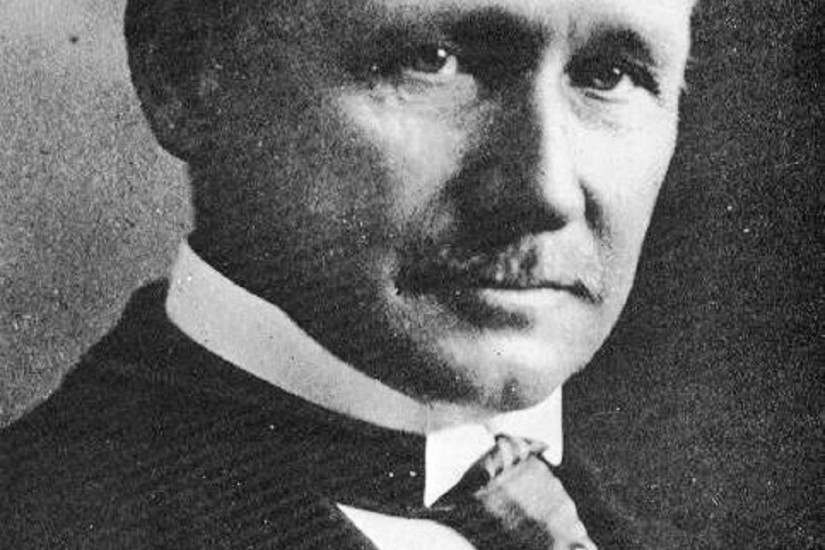

Scientific management is often associated with the work of Frederick Winslow Taylor, who was born into a respectable Philadelphia family in 1856. Though he won admission to Harvard University, he became a lathe operator at Midvale Steel Works, a company known for producing high-end steel armaments, steam turbines, and other products that required utter precision.

William Sellers, the famed engineer who ran Midvale, was obsessed with the idea that his collection of workers and machines could function as a single organism bendable to his will on a daily basis. “He knew how to give an order and exact obedience,” recalled one associate after his death, “and only to those who showed the capacity to obey did he extend the authority to direct the management of his affairs, while over all he never failed to exercise a masterly control.”

Taylor was cut from the same cloth. As he moved up the ranks at Midvale, he spearheaded a series of experiments on the shop floor, trying to find cut the amount of time it took to do certain tasks.