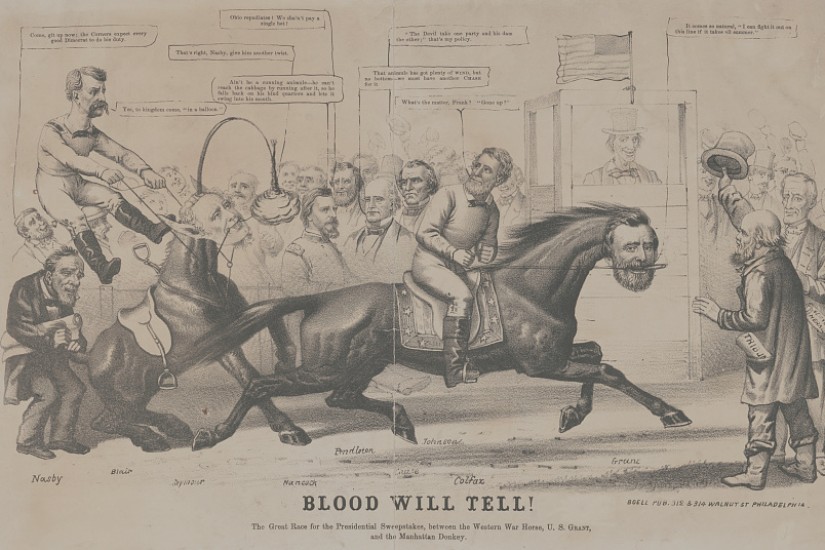

As we reflect on Reconstruction and its international resonance, we might recall a specific moment – the election of 1868. In November of that year, the United States held the first national election in which African American men in the former Confederacy could vote, introducing a new and potentially powerful force in electoral politics. The election came on the heels of a momentous few years. The Republican Congress had wrested control of Reconstruction from President Andrew Johnson. The Reconstruction Acts of March 1867 had set in motion the expansion of suffrage in the South and prescribed the process for adopting new state constitutions. In the spring preceding the presidential election, an impeachment trial narrowly resulted in Johnson’s acquittal. In the South as election day approached, the Ku Klux Klan (founded in 1866) waged a campaign of terror, targeting African Americans and white Republicans.

International observers, particularly within the British government, were riveted by these events and the prospect of a tumultuous election. British officials’ own domestic, imperial, and diplomatic preoccupations drove their profound interest in American politics. At the time of Radical Reconstruction, British politicians and intellectuals were in the throes of reassessing British institutions and debating the organization and representation of the colonies. At home, the Reform Act of 1867 had almost doubled the British electorate. Although hailed as the “Leap in the Dark,” this legislation retained significant restrictions on the franchise and was far more limited than the changes underway in American governance. Looking to the United States as a laboratory in which to watch political experiments unfold, British officials speculated about where the expansion of American democracy might lead and how it would alter the nation’s role in the international sphere. Marveling at the rapidity and unpredictability of developments in the United States, they worried about how these changes might disrupt the British Atlantic. One prominent British cabinet member observed, “On the whole the American Revolution (for the practical change in their government amounts to nothing less) is watched with more interest than any other event of the moment.” He added, “It is hard to see how a majority of Congress, with the president in opposition, is to govern a conquered country half the size of Europe yet this they must do or fail.” British leaders’ calculations about a shifting international order drew on their interpretation of changes in the relationship between the federal government of the United States and the American electorate and public.