As Election Day approached and white Democrats prepared themselves for a pitched battle, “radicals” at Belmont, led by two men, Isaiah and Mac, were organizing on the plantation in preparation for voting the Republican ticket. They had plans to “meet at the creek tomorrow night,” Gertrude was informed, “to march to town the next day with Uncle Isaiah as captain.” “Things are rapidly approaching a crisis,” she noted two days before the election. “It is reported that all of the houses in the neighborhood are to be burnt up.” Her informant among the Belmont freed people, a teenager named Ned, told her that “Uncle Mac said if he had a son who was willing to be a Democrat he would cut his throat.”

Arrayed against each other, and amid rumors of violence and arson, white and black at Belmont prepared for the coming fight. The night before the election, Jefferson Thomas went out to patrol with the local militia company, “of which he is captain,” his wife noted proudly. Before he kissed her goodbye, he asked to have his guns brought up. There they sat, stacked in the corner of the kitchen. When her husband left, Gertrude expressed her hope that that there would be “no necessity for force…Only absolute necessity [would cause] Southern men to resort to force,” she noted that night. It was a claim refuted by a long history.

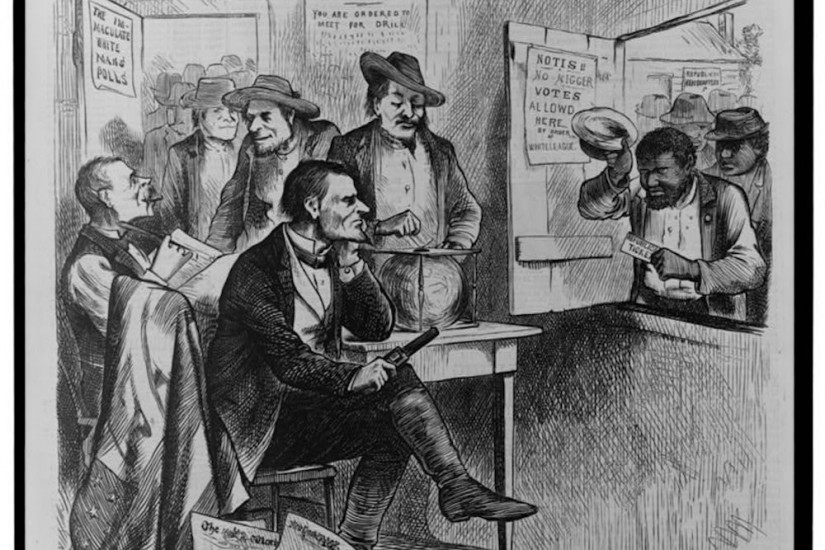

The Negro Disfranchised, from “Tragedy of the Negro in America: A Condensed History of the Enslavement, Sufferings, Emancipation, Present Condition, and Progress of the Negro Race in the United States of America.” The New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

On Election Day, everyone girded for violence. “No wonder the great heart of the South throbs at the thought of how much will depend upon the vote of today,” Gertrude noted nervously that morning. “Mr. Thomas went to Pine Hill to vote,” she added. “Mr T.” would have a leading role to play, as she knew: he was “captain of the [militia] company in Augusta,” and in this neighborhood “president of the Democratic club.” It was a damning admission, as Virginia Burr, the editor of Thomas’ diary, was quite aware. Burr omitted that entry entirely from the published diary, as she did earlier references to Jefferson Thomas’ role as captain of the militia during the violent campaign of voter suppression and a later one to Gertrude’s brother Buddy, known by local black Republicans as “one of the Ku Klux.” The published diary has been scrubbed clean. Those critical entries lie buried among more than two thousand manuscript pages in the Rubenstein Library at Duke University.

Freedmen Voting in New Orleans, 1867. The New York Public Library, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs. That campaign of political violence not only reached, but also radiated out from, Gertrude and Jefferson Thomas’ home plantation.

Freedmen Voting in New Orleans, 1867. The New York Public Library, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs. That campaign of political violence not only reached, but also radiated out from, Gertrude and Jefferson Thomas’ home plantation.