Turns out our current use of Florida as national outlier has quite a long history. Michele Currie Navakas’s Liquid Landscape: Geography and Settlement at the Edge of Early America convincingly demonstrates that Florida has always — and importantly — compromised master narratives of US nationalism. In this meticulously curated monograph ranging from the colonial era through the early 20th century, Navakas marshals evidence from explorers, cartographers, botanists, geologists, and imaginative writers to support a compelling interdisciplinary argument concerning the centrality of Florida’s peculiar position in North American history. Demonstrating the centrality of Florida in shaking up conventional conceptions and rhetorics that have undergirded property ownership, national expansion, and domestic practices ever since the Enlightenment, Navakas foregrounds a distinctive Florida environment — its marshes, hammocks, reefs, and shoals — as one of the strongest checks on national incorporation and its imperial ambitions. As critics continue to challenge the organizing myths of the US nation and the “roots and routes” of its literary history, Navakas adds an important and impressive new study to the conversation. As it turns out, Florida’s long-term weirdness is kind of a good thing.

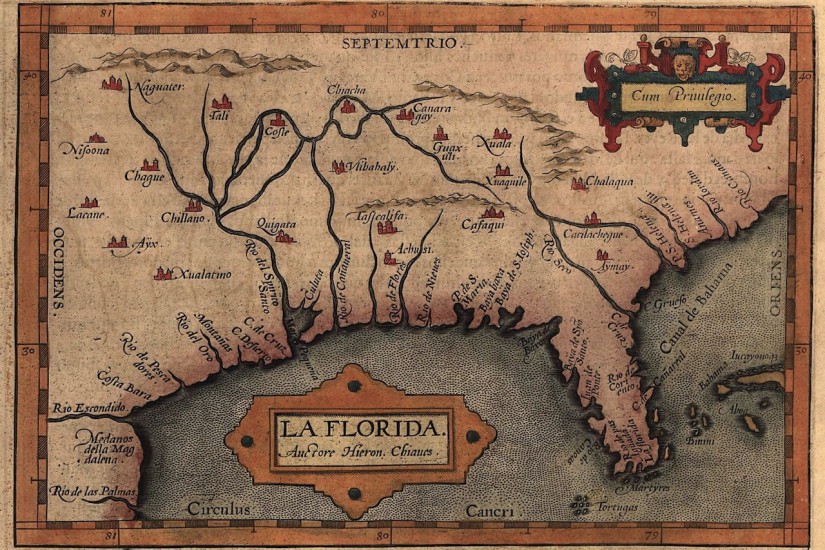

“What does it mean to take root on unstable ground?” With this opening question, Navakas points out that all the Enlightenment principles that British settler-colonialists brought to North America in the 17th century met unexpected challenges in Florida. While the increasingly valuable peninsula had been inhabited for thousands of years prior to British arrival, Florida-dwellers did so without the more familiar principles of possession, enclosure, and development that came to be the norms for both property ownership and political rights in the early United States. With US expansion into the Mississippi Valley and the increased importance of Florida as gateway for commerce in the Gulf of Mexico, the unique landscape inspired widely read works in which authors imagined alternative terms for settlement, for belonging, and for claiming roots. “To many early Americans,” Navakas writes, “the liquid landscape appeared not as an obstacle to settlement, but rather as a provocation to think beyond more familiar ideals of land and boundaries that made it possible to imagine the United States as settler nation and empire in the first place.” While some might assume Florida to be simply a minor exception in the master narrative of US incorporation and merit scholarly assessments as regional outlier, Navakas makes a strong case that “Florida’s fundamental porosity and dispersal made it part of North American thinking about personal, national, and imperial identity even before there was a coherent nation […] [Furthermore,] these seeming peripheries of early America should matter more centrally to our own scholarly understanding of early U.S. literature and culture.” With confusion about the actual topography of Florida in the early colonial periods — some cast it as an island or group of islands, some thought it a more conventional peninsula — as well as the lifestyles of the highly mobile indigenous populations, the peninsula endured different periods of European rule: by the Spanish from 1565 to 1763, by the British from 1763 to 1783, by the Spanish again from 1783 to 1821, and finally by the USA from 1821 on. As Navakas cannily demonstrates, few imperial rulers had much success in securing a stable hold on the shifty land and its recalcitrant peoples. Due to Florida’s perpetual undermining of a cohesive master narrative of US continental mastery, Liquid Landscape makes a case for itself by stating that “no other North American ground combined topographic instability, geographic indeterminacy, and demographic fluidity as obviously and dramatically as Florida.”