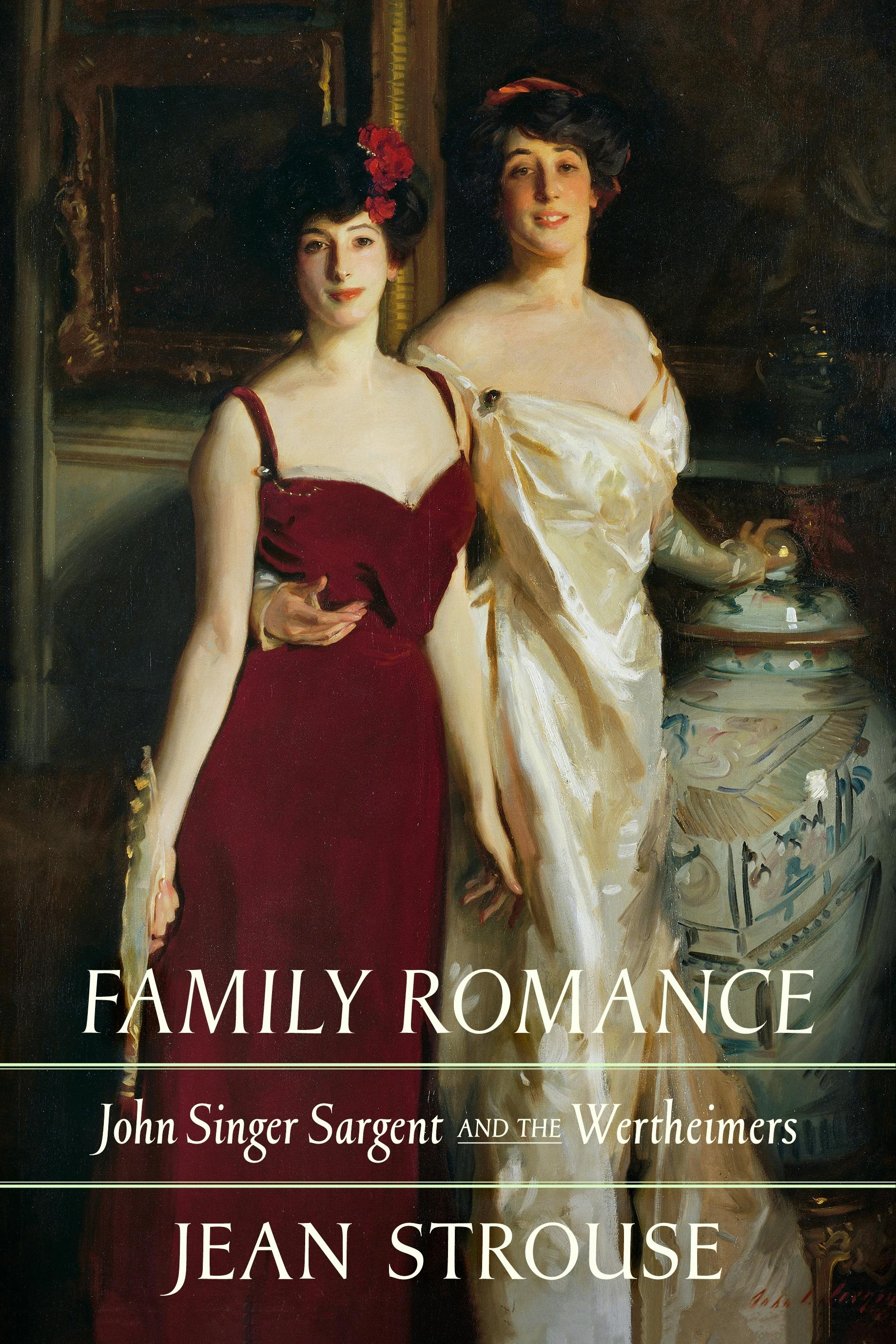

In 2001, the biographer Jean Strouse happened upon an exhibition of paintings by John Singer Sargent that featured twelve portraits of the Wertheimers, a British family of German-Jewish descent. Asher Wertheimer, the patriarch, was a well-known art dealer who had commissioned Sargent to paint a series of portraits of himself and his wife in 1897 to commemorate their twenty-fifth anniversary. Over the next decade, as the artist painted the couple and their ten children—individually and in groups, sometimes more than once—he evidently got to know the family well. A photograph on display alongside the portraits showed him playing croquet with two of the Wertheimers on the lawn of their country house.

At the sight of the portraits, Strouse was “entirely captivated,” she writes in her introduction to Family Romance: John Singer Sargent and the Wertheimers. It’s a type of coup de foudre that might be unique to biographers, who must be prepared to devote years, if not decades, to their subjects. As Strouse wandered the gallery, her mind filled with questions. Who were the members of this family, whose portraits represented them as both “distinctively Jewish” and members of London’s upper class, surrounded by items that testified to their luxurious lifestyle? What were their lives like in a society that perceived Jews as irremediably “other,” regardless of their wealth and education? And how had Sargent, an American expat and “cosmopolitan nomad,” come to paint them?

But perhaps Strouse’s most important question, at least in the context of the project upon which she felt drawn to undertake, was a practical one: Was there enough material here for a book? Her two previous biographies had drawn on significant archives. Her debut was a life of Alice James, the invalid sister of novelist Henry and philosopher William, whose accomplishments were undistinguished but in whom Strouse found an exemplar of others of her class and station: women with ambition and intelligence who had few options outside the domestic sphere. Quiet, nuanced, and probing, Alice James became an instant classic upon its publication in 1980, and it has been an inspiration to feminist scholars ever since. (The book was reissued last month by Picador.)

Some biographers stick with the same time period or intellectual world, choosing a future subject from the circle that surrounds a previous one. For her second book, Strouse has said, she wanted “a complete change.” She found it in the life of the American financier J. Pierpont Morgan, whose papers, still uncatalogued, were waiting for her at the Morgan Library in Manhattan. Here the challenge was quite different. Strouse didn’t need to make a case for the significance of her subject; Morgan’s myth was already larger than life. The image of him as a cynical, rapacious tycoon who had single-handedly shaped the American economy around his own whims was well established.