Some time ago, I wrote a blog post about a hypothesis I had regarding President Truman and the decision to use the atomic bomb. My basic thesis then (and continues to be) is that there is good reason to think that Truman did not understand that Hiroshima was a city with a military base in it, and not merely some kind of military installation. Truman’s confusion on this issue, I argue, came out of his discussions with Secretary of War Henry Stimson about the relative merits of Kyoto versus Hiroshima as a target: Stimson emphasized the civilian nature of Kyoto and paired it against the military-status of Hiroshima, and Truman read more into the contrast than was actually true.

I have kept poking around this issue for some time now, and written an article-length version of it (more on that in due time). I feel even more confident in it than before, having gone over the relevant documents very closely and talked about with many scholars (including at a conference in Hiroshima last summer), though there are some aspects of the original blog post that I would refine or revise.

But I thought I’d share one set of documents that I found extremely illuminating and interesting, and useful for thinking about how the “narrative” of Hiroshima changed over a very short period of time in August 1945. I have not seen any reference to these in the work of any other historians, not because they are slouches (they are not), but because you have to be asking very specific questions to think they are a possible source of the answers.1

The press release sent out under Truman’s name after the bombing of Hiroshima was not written by him. It was largely written by Arthur Page, a Vice President at AT&T and the “father of modern corporate public relations,” at the request of the Interim Committee of the Manhattan Project. Page was an old friend of Henry Stimson, the Secretary of War, and Stimson wanted the first statement to be a very carefully-written document, as it was meant to credibly describe a new weapon and outline possible paths forward for the Japanese. Truman was shown the final version of it, but he didn’t add or remove anything from it. It is interesting (for my purposes) to note that if you did not know whether Hiroshima was a city or an isolated military base, the initial announcement would not clarify that for you, even if you were (like Truman) the one reading it aloud.

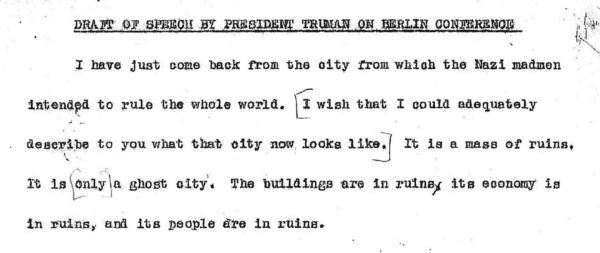

A far more interesting case is the second speech that Truman gave which mentioned the atomic bomb. This was a radio address given on the evening of August 9, 1945, not long after the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. The atomic bomb only occupies a small part of the overall speech — it is really a speech about what had happened at the Potsdam Conference the weeks previous. But the parts on the atomic bomb are fascinating to read. Here are the parts I’d like to draw your attention to in particular:

The world will note that the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, a military base. That was because we wished in this first attack to avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of civilians. But that attack is only a warning of things to come. If Japan does not surrender, bombs will have to be dropped on her war industries and, unfortunately, thousands of civilian lives will be lost. I urge Japanese civilians to leave industrial cities immediately, and save themselves from destruction. […]

Having found the bomb we have used it. We have used it against those who attacked us without warning at Pearl Harbor, against those who have starved and beaten and executed American prisoners of war, against those who have abandoned all pretense of obeying international laws of warfare. We have used it in order to shorten the agony of war, in order to save the lives of thousands and thousands of young Americans.2