By the time of The Scarlet Letter’s publication, the practice of abortion had expanded into a thriving business, generated by advertising and transforming into a lucrative area of medical specialization. As historian Janet Farrell Brodie explains in her preface to Contraception and Abortion in Nineteenth-Century America, “What began in the 1830s as the focus of a small group of social and health reformers—Robert Dale Owen and Charles Knowlton especially—by the 1860s was the province of a diverse assortment of entrepreneurs and businesspeople.” And, reflecting on the drop in the white birth rate of the time, Brodie demonstrates that the demand for abortion and contraception produced the supply, which in turn produced more demand: by virtue of this back-and-forth process, white marital fertility declined in the antebellum period, a pattern that continued through the century. According to historian James Mohr in Abortion in America, “One indication that abortion rates probably jumped in the United States during the 1840s…was the increased visibility of the practice. It is not unreasonable to assume that abortion was more visible at least in part because it had become more frequent. And as it became more visible, more and more women would be reminded that it existed as a possible course of action to be considered.” For Mohr, a “dramatic surge of abortion” took place after the 1830s, attributable to its commercialization and to the desire of women (primarily married white Protestant women) to delay or prevent childbearing. In light of this context, the story of Pearl’s birth is interlineated not only with illegitimacy but also with contingency.

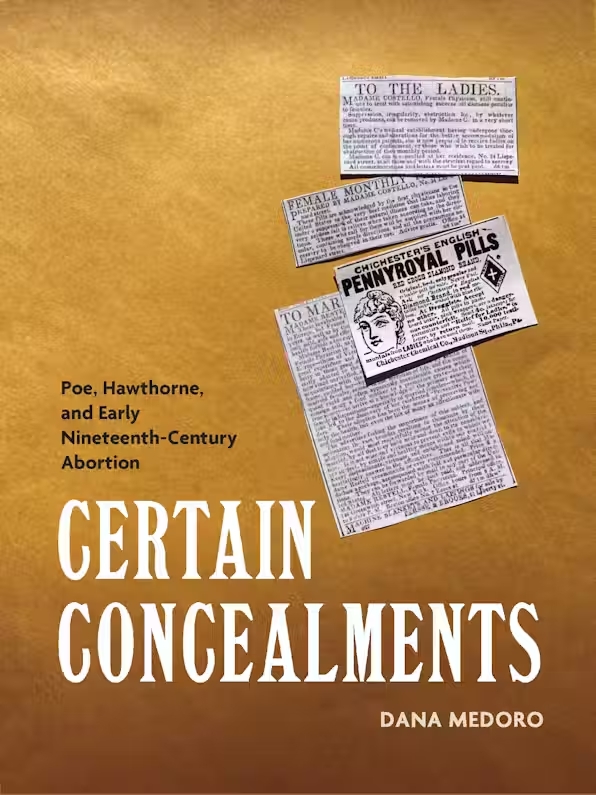

As the National Police Gazette indicates, attempts to put the practice of abortion outside of women’s reach repeatedly failed. With the abortionists “still at work” despite the law, their influence and services proliferated as the kind of open secret to which Hawthorne was drawn. Women knew how to procure what they needed and how to read the abortionists’ advertisements, even as those advertisements became increasingly oblique. Indistinct references to menstrual-cycle obstructions, for example, brilliantly evaded censure while delivering the necessary information for obtaining cures.

At the same time, those who opposed the practice introduced more strident terms, shifting any ambiguity surrounding pregnancy and abortion into definitional clarity. In 1844 the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal carried this announcement about abortionists: “The law has not reached them…Their trade in infanticide is unquestionably considered, by these thrifty dealers in blood, a profitable undertaking.” Equating abortion and infanticide, the journal’s editorialist here followed the lead of physician Theodric Beck, whose multiply reprinted Elements of Medical Jurisprudence placed abortion as a subsection of his chapter on infanticide and outlined the methods by which both crimes could be detected.