How did you first hear about the hero of your book?

Stephanie St. Clair entered my life thanks to my mother. She’s from Martinique herself, and she tirelessly advocated for us to know our history and the figures that came before us. Through her, my sister and I learned of Césaire, Fanon, and numerous figures from Martinique who played a role in our culture. At first glance, Stephanie and my mother share only a birthplace. Stephanie was cunning—even ruthless—and a notorious racketeer. However, she was also a powerful Black woman taking control of a world run by men, who refused to let the cards she was dealt stop her from dreaming big and achieving big. I wonder whether my mother felt a kinship with her because of this.

What does it mean to you to amplify a little-known story such as Queenie’s? What do you think is lost when history erases figures like her?

A core part of my practice is dedicated to shedding light on Black figures who have been overlooked or even entirely omitted from historical narratives, and finally rendering them visible. When your history has been erased, how do you learn about your ancestors? How do you learn from the past—let alone determine its effect on our present? How do you celebrate the stories that made you? How do you belong?

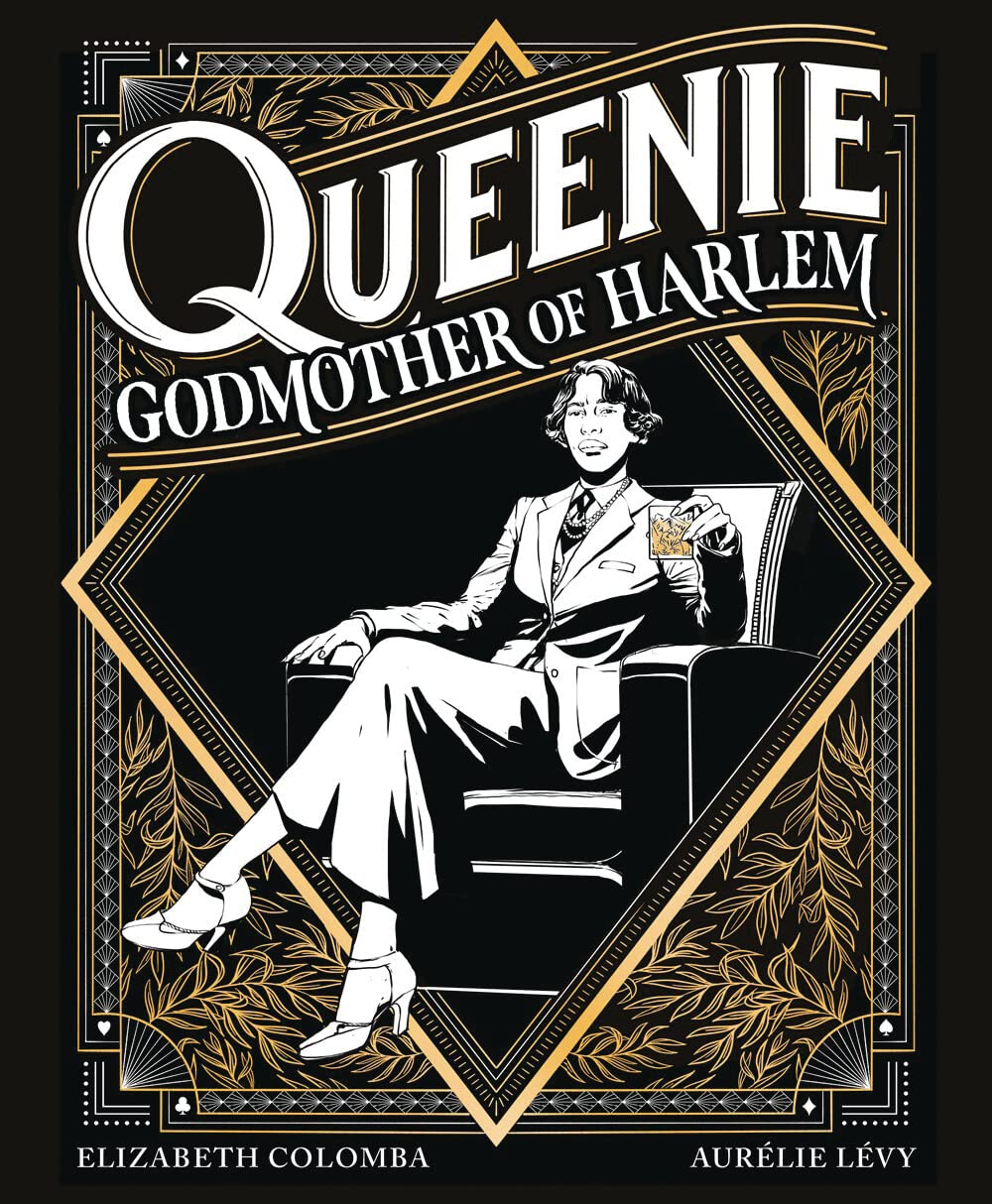

Queenie is not only seldom credited or mentioned, but, as is too often the case, it is a male counterpart whose name we remember: her protégé Bumpy Johnson. Yet it is because of her tutelage that he was built at all. To recenter the spotlight on her—her audacity, her daring, her drive—and reinscribe her into the historical conversation is also to reconnect ourselves to our own cultural footprint.

History should be an objective study, but it is all too vulnerable to ideologies and ulterior motives. Erasing the contributions of Black figures across history only cheats us of the complete story. We all become richer by restoring our legacy.

Your fine-art work reimagines Black people in classical art, often in the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries. What was it like to dive into the nineteen-thirties for this book?

Whether for painting or for this new medium, I take immense pleasure in collecting information. As my writing partner, Aurélie Lévy, and I worked on scenes, we found ourselves checking every single element for historical accuracy: Did cars have a radio? Was this song from this era? Was the subway a possibility?