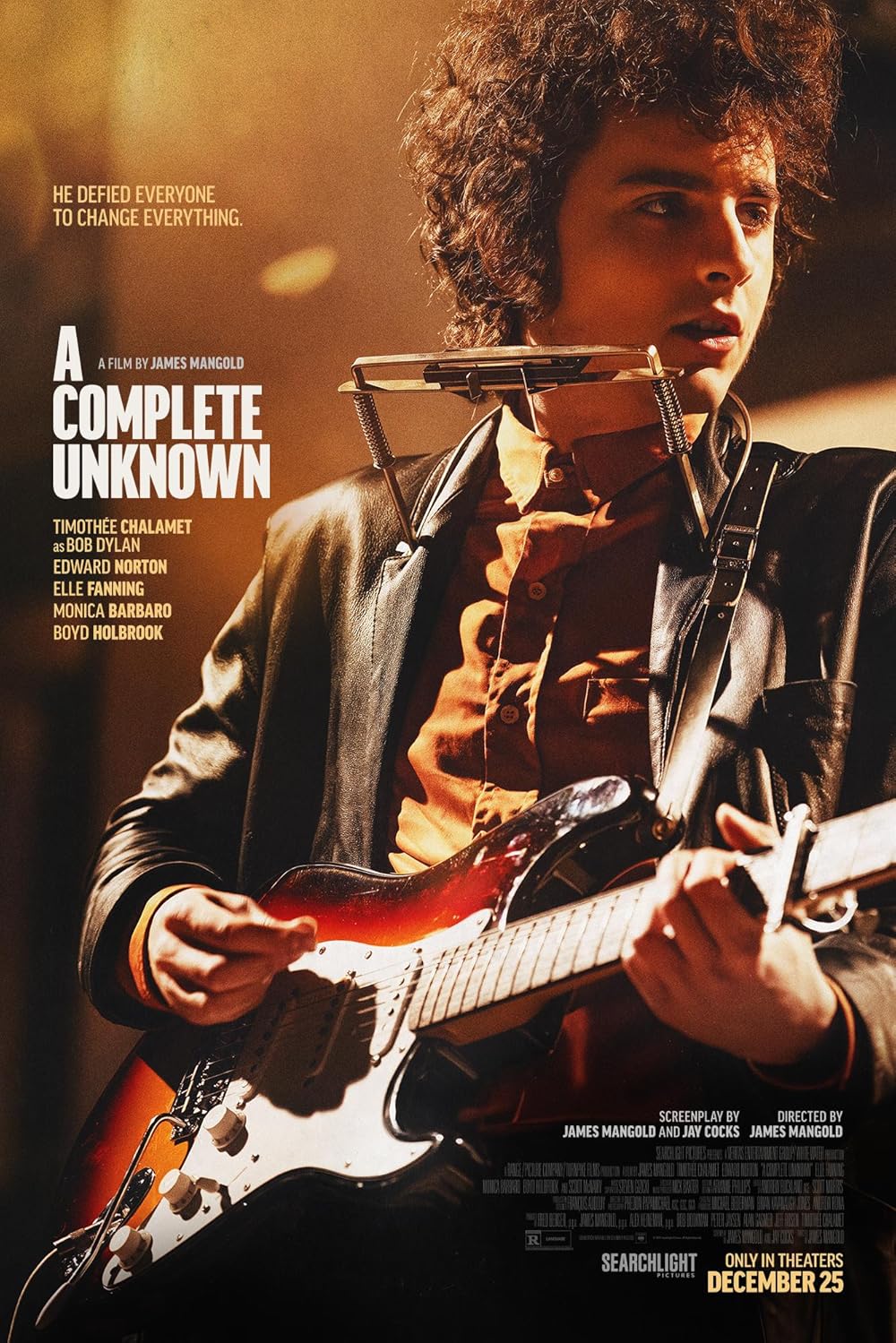

Toward the end of A Complete Unknown, the new film chronicling Bob Dylan’s early career, Pete Seeger and the young Dylan have a quiet but tense encounter. Anticipating Dylan “going electric” at the 1965 Newport festival, Seeger offers Dylan an extended metaphor about people working together for social justice, each person bringing a spoonful of sand to outweigh the force of injustice. Dylan, says Seeger, brought a shovel, with his powerful folk songs like “Masters of War” and “The Times They Are A-Changing.” Dylan rejects Seeger’s sermon, takes the stage, and blasts the old folk establishment with his electric Stratocaster.

According to the film, the Seeger-Dylan clash reflects the broader conflict between a musical tradition born out of the Old Left that brought together folk music and social justice causes, and the rise of a new musical sound, more experimental, far less political, and more closely keyed to the angry emotions of young Americans. It was, claims the book on which the movie is based, “the night that broke the Sixties.”

Not quite. There were a lot of things that “broke” the 1960s besides rock and roll: Black Power, Second Wave Feminism, drugs, and perhaps most significantly, the war in Vietnam, which also divided the folk music world. While popular memory of the 1960s assumes that folk fans and performers marched hand-in-glove with the anti-war protesters of the 1960s, in reality, the political climate of that moment, as well as the intensified commercialism of folk music, disrupted that alliance.

I have a historical interest in these events, and also a personal connection. My father, Irwin Silber, co-founded Sing Out! magazine in 1951, along with his close colleague, Pete Seeger. By the late 1950s, Sing Out! had become the go-to magazine for countless folkies—like the popular folk trio of Peter, Paul, and Mary; newer performers like Tom Paxton; and the “star” of the folk movement, Joan Baez. Long involved with left-wing causes, Sing Out! was also aligned with struggles for racial justice and international peace. My father wrote an irritated critique of Dylan in November 1964, chiding him for turning away from “protest” songs as he became more attached to the “paraphernalia of fame.”

But what concerned him most, in the summer of 1965, was not Dylan, but Vietnam. LBJ, having secured congressional backing in 1964 to promote U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia, had dramatically increased U.S. troop presence in Vietnam from 23,000 to 184,000 and began an intense bombing campaign against North Vietnam in February.