Marching through somber streets, men in uniform confiscate items, entering houses for further looting, all legalized by a leader waving his fist and spewing anger. Germany in the 1930s? No, the classic Christmas movie Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town, which aired originally in 1970.

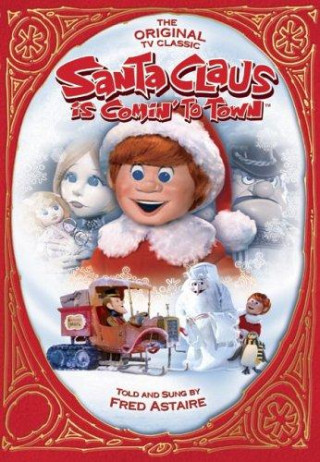

Written and directed by the men who brought Americans Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer, Frosty the Snowman, and the Little Drummer Boy, Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town was a classic story of good versus evil. It used Nazi imagery and symbolism to craft an origin story for Santa Claus—the story’s hero and the pinnacle figure of capitalist, secular Christmas. Needing an antihero for Santa to thwart, the film capitalized on a decade in which news stories, early Holocaust scholarship, and representations in popular culture made Americans far more aware of the Nazis and their heinous crimes. Many Americans have watched it almost every year since.

Yet, while the story is beloved, it points to a cultural problem that has helped perpetuate antisemitism. The movie reminds Christian Americans of the Nazi crimes and uses them to convey villainy, without engaging antisemitism or Jewish people at all. Christmas presents, not Jewish people, are the victims of the vaguely German antihero. This is a common practice in movies, television, and novels, and it has left Americans understanding the evil of the Nazis without fully grasping who they targeted, why, and how the antisemitism at the root of the Holocaust continues to reverberate for Jewish communities around the world.

Despite early efforts after World War II to punish the Nazis, such as the Nuremberg Trials, as well as the creation of the state of Israel, collective memory of the era failed to grasp fully the horrors of the genocide perpetrated against Jewish people. One problem was that some audiences Christianized the victims to be able to empathize and identify with the tragedy.

In the 1950s, the reaction to the best-selling The Diary of a Young Girl epitomized how popular memory of the Holocaust was incomplete, with the public not reckoning with the full scope of the Nazi atrocities — especially who the victims were and why they were targeted. Readers tended to ignore Anne Frank’s Jewishness, viewing her as Anglicized and as forgiving them: “In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart,” Frank wrote before having seen a death camp.