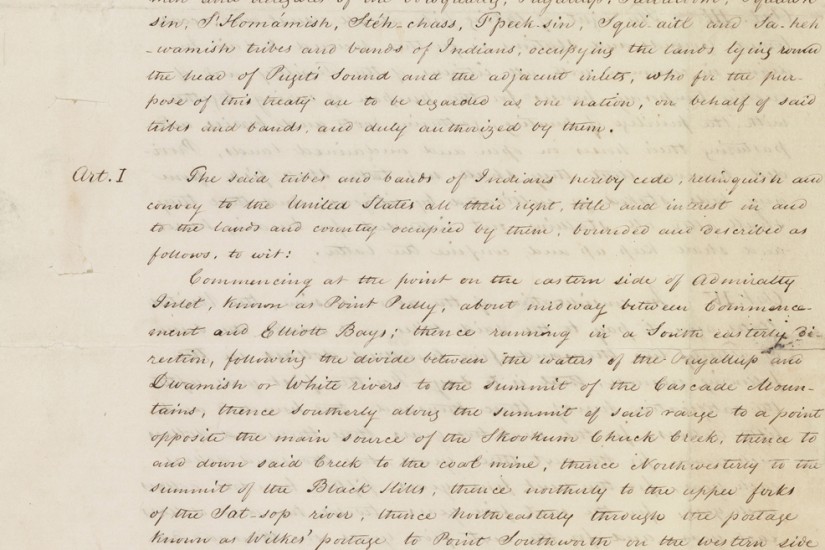

The Medicine Creek treaty arose out of a series of treaty councils in the winter of 1854 held by the new governor of Washington Territory, Isaac Stevens. As in other areas of the West, white settlers and prospectors wanted the land occupied by the Indians. Stevens was negotiating the terms and eyeing some 4,000 square miles of fertile lands around Puget Sound and its tributaries, tribal home to the native Indians.

Scholars are somewhat divided on who came up with the idea of offering fishing and hunting rights in exchange for the land. Mark Hirsch, a historian at the museum, says it is clear that a month before any sit-downs with the tribes, Stevens’ notes indicate he had decided that guaranteeing traditional hunting and fishing rights would be the only way the Indians would sign an agreement. The language was drafted before the treaty councils, says Hirsch. “They’ve got it all written out before the Indians get there,” he says.

It is an agreement that is continuously tested. Today, the Medicine Creek treaty rights are under threat again from a perhaps an unforeseen enemy: climate change and pollution, which are damaging the Puget Sound watershed and the salmon that breed and live in those rivers, lakes and streams.

“It’s tough because we’re running out of resources,” says Nisqually tribal council member Willie Frank, III, who has long been active in the modern-day fishing rights battle. “We’re running out of salmon, running out of clean water, running out of our habitat. What we’re doing right now is arguing over the last salmon,” he says.

The history of Indian treaties is littered with broken promises and bad deals. And even though Medicine Creek was disadvantageous in many ways, “it’s all we’ve got,” says Farron McCloud, chairman of the Nisqually tribal council.