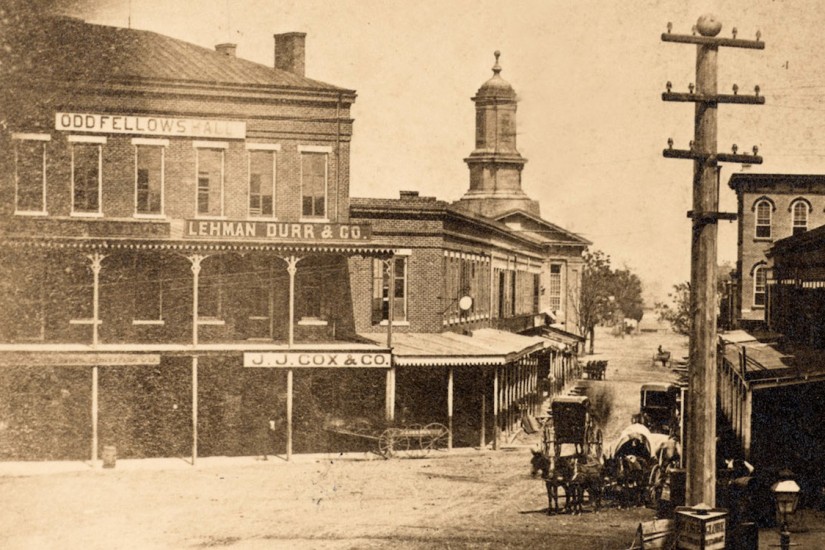

In 2013, the Italian playwright Stefano Massini turned this exemplum into The Lehman Trilogy, an epic five-hour play that was adapted and condensed last year by the director Sam Mendes and playwright Ben Power for the National Theatre in London. The play received rapturous reviews, and further plaudits after a limited run this spring in New York; it has just returned to London’s West End, where its continued success seems assured. The story begins in 1844, when Hayum Lehman emigrated from Bavaria to Mobile, Alabama. He changed his name to Henry and worked as an itinerant peddler before opening a small dry-goods store upriver, in Montgomery. Soon, two of his younger brothers, Mendel (Emanuel) and Mayer, joined him, and the dry goods store gradually evolved, first into a brokerage, and then into a bank. The play presents this arc as a parable of moral decline, from selling “goods,” to selling financial abstractions. “We are merchants of money,” second-generation Philip Lehman declares in Power’s translation: “our flour is money.”

The drama built around this story is an impressive theatrical experience, but also a deeply partial one, as some critics have noted—for the simple reason that some of the “goods” originally traded by the Lehman brothers, before their spiritual decline into mere merchants of money, were human beings. The play acknowledges, briefly, the company’s origins in the cotton markets of the antebellum South—profoundly underplaying not only the firm’s deep entanglement in the slave economy, but also that of the brothers themselves, who held slaves for at least twenty years. When I was invited by the National Theatre to write for its playbill an essay about the Lehman brothers as exemplars of the American Dream, my original draft mentioned the brothers’ connection to slavery, but this was cut from the final edit. When New York’s Park Avenue Armory asked if they could reuse the essay, I inquired if we could restore the issue of slavery, and offered an expanded draft with more detail. They preferred the National Theatre’s version, citing length.

The elision is not sinister, but it is symptomatic. No one involved in editing the playbills is defending or apologizing for slavery; they were doing their jobs, putting together a program of necessarily brief essays about the play as it has been produced, which does not address slavery. But the erasure of slavery from the play matters: it distorts the history of Lehman Brothers’ beginnings in the antebellum South, allowing the play to evade the question of whether making money out of money is really more reprehensible than making money out of slaves. That erasure is, ironically enough, perhaps the most allegorical aspect of the entire story: a history of American capitalism that disavows the central role slavery played in that history.