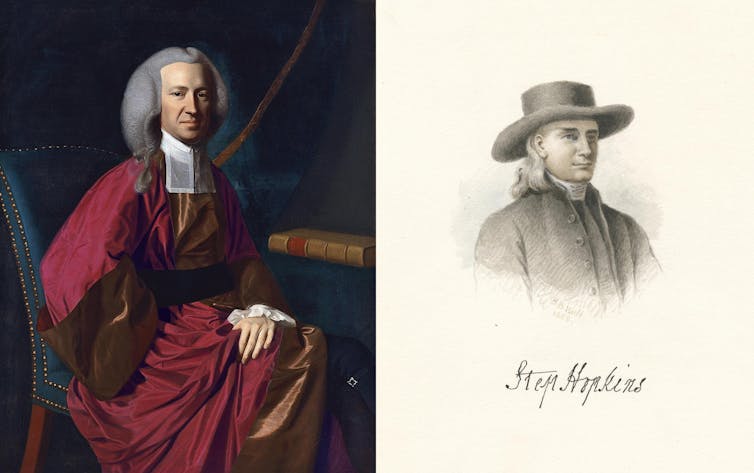

Through the early 1750s, two men in the British colony of Rhode Island – Martin Howard and Stephen Hopkins – had similar backgrounds and led strikingly similar lives. They knew each other, were both supporters of libraries with successful legal careers, and were politically active.

Their writings in the 1760s demonstrate that they were both assessing the political relationship between the North American colonies and Britain.

Both men claimed that they felt truly British – but from their shared identity they arrived at violently opposing conclusions.

My historical research into Rhode Island’s politics and economics during the colonial period has found these two men’s approaches to the issues of the day are a microcosm of the decisions faced by thousands of British colonists on the eve of the American Revolution.

And they are a lesson about how what might appear to be common values about shared political and cultural identities can at times serve not as a bridge joining people together but a wedge driving them apart.

Parallel paths

The stories of Martin Howard and Stephen Hopkins begin as mirror images of each other, including growing up in Rhode Island.

Howard worked as an attorney in his hometown of Newport. The Newport Mercury newspaper chronicles his many civic and political activities. He served as Overseer of the Poor, Smallpox Inspector, and in the Rhode Island General Assembly. In the early 1750s, he served as the librarian at Newport’s Redwood Library. And he was one of two men elected to represent Rhode Island at the 1754 gathering of representatives from the northern colonies known as the Albany Congress.

Hopkins, for his part, became a justice of the peace in Scituate, Rhode Island, in 1730, and served multiple terms as Rhode Island’s governor in the mid-18th century. In 1753, he was a founding member of the Providence Library Company. And he was the other Rhode Island representative at the Albany Congress in 1754.

In the early 1760s, their paths might have seemed closely aligned. But then, in 1763, everything changed.

That year, the Treaty of Paris ended the Seven Years’ War – known in the American colonies as the French and Indian War, and called “the first world war” by historian and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. At the end of a multinational conflict spanning continents and oceans, Britain took over almost all of France’s territory and trade in North America and India. But the triumphant empire had incurred enormous debts to fund its war effort.

Seeking to repay its debts and expand its North American influence, the British Parliament passed the Sugar Act in 1764 and the Stamp Act in 1765.

These laws imposed significant tax burdens on colonists, though they had no representatives in Parliament to voice their concerns. Howard’s and Hopkins’ reactions to these laws marked a key phase of division between them, and across colonial North America.

Dueling pamphlets

Most political activity in the late 18th-century Anglo-American world was fueled by private groups who advocated for a wide range of causes.

Howard was a founding member of the Newport Junto, which supported both the Sugar and Stamp acts and advocated for Rhode Island to come under greater Parliamentary control. Hopkins supported the loose coalition of organizations collectively known as the Sons of Liberty who campaigned against imperial taxation.

Many members of these groups turned to the printing press to reach audiences across the Atlantic world. Rhode Island had two printing presses: Howard published his ideas via the Franklin-Hall press in Newport, while Hopkins used the Goddard press in Providence.

A close read of the pamphlets published by Howard and Hopkins in the mid-1760s shows they both invoke their common Anglo-American heritage – but only one would eventually come to the conclusion that it was necessary to sever that link.

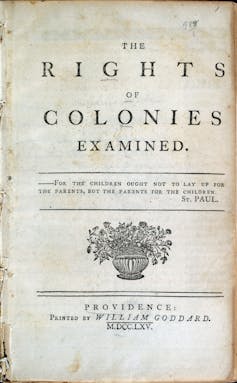

For example, in November 1764, Hopkins published a pamphlet entitled “The Rights of the Colonies, Examined.” It began with the premise that because he was a British subject, he was entitled to all the relevant rights and privileges those subjects held. To him, that included the right to have a voice in Parliamentary deliberations about colonial taxation, because he lived in Britain’s North American colonies.

Less than two months later, in January 1765, Howard published a reply: “A Letter from a Gentleman at Halifax to his Friend in Rhode Island, Containing Remarks Upon a Pamphlet Entitled ‘The Rights of the Colonies, Examined.’” Like Hopkins, he began with the premise that because he was a British subject, he was entitled to all the relevant rights and privileges. But in Howard’s view, this did not include a right to vote in Parliamentary elections: Not all British people could vote, even if they lived in Britain.

A split based on shared identity and values

The distinctions between the rhetoric of Hopkins and Howard are representative of those between most British North American colonists in the 1760s. Howard and others who wanted to remain subject to the crown continued, through the end of the American Revolution, to believe that their rights were untrammeled. By contrast, Hopkins and the other proponents of revolution with Britain would come to believe in the mid-1770s that the only way to preserve their rights and privileges was to break away completely from the United Kingdom.

It was a revolution, but those who sought to break from Britain did so as a way of preserving their British identity. This seeming contradiction helps illustrate why groups of people who shared Anglo-American identity and heritage fought on both sides of a violent war to preserve their divergent views of that identity and heritage.

The story of Hopkins and Howard ends on either side of a divide as geographic as it was political, with Howard in permanent exile in London, and Hopkins, having signed the Declaration of Independence, living in the Rhode Island town where he was born – in the smallest of the British North American colonies, which had become the smallest state in the United States of America. Nevertheless, the commonalities between them remain as important as the differences, and truly understanding their story requires keeping both elements in mind.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.