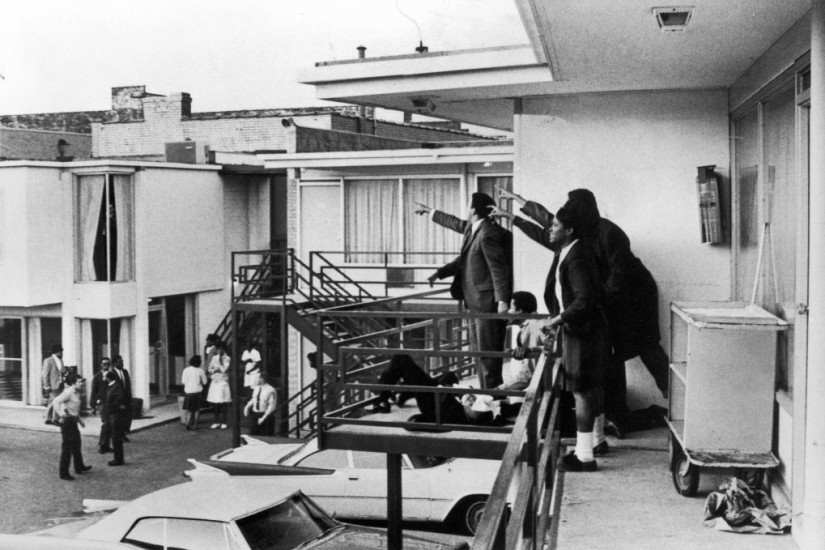

Images aside, what was it really like to experience 1968? Public life seemed to become a sequence of ruptures, shocks, and detonations. Activists felt dazed, then exuberant, then dazed again; authorities felt rattled, panicky, even desperate. The world was in shards. What were for some intimations of a revolution at hand were, for exponents of law and order, eruptions of the intolerable. Whatever was valued then appeared breakable, breaking, or broken.

The texture of these unceasing shocks was itself integral to what people felt as “the 1968 experience.” The sheer number, pace, volume, and intensity of the shocks, delivered worldwide to living room screens, made the world look and feel as though it was falling apart. It’s fair to say that if you weren’t destabilized, you weren’t paying attention. A sense of unending emergency overcame expectations of order, decorum, procedure. As the radical left dreamed of smashing the state, the radical right attacked the establishment for coddling young radicals and enabling their disorder. One person’s nightmare was another’s epiphany.

The familiar collages of 1968’s collisions do evoke the churning surfaces of events, reproducing the uncanny, off-balance feeling of 1968. But they fail to illuminate the meaning of events. If the texture of 1968 was chaos, underneath was a structure that today can be—and needs to be—seen more clearly.

The left was wildly guilty of misrecognition. Although most on the radical left thrilled to the prospect of some kind of revolution, “a new heaven and a new earth” (in the words of the Book of Revelation), the main story line was far closer to the opposite—a thrust toward retrogression that continues, though not on a straight line, into the present emergency. The New Deal era of reform fueled by a confidence that government could work for the common good was running out of gas. The glory years of the civil rights movement were over. The abominable Vietnam War, having put a torch to American ideals, would run for seven more years of indefensible killing.

The main new storyline was backlash. Even as President Nixon assumed a surprising role as environmental reformer, white supremacy regrouped. Frightened by campus uprisings, plutocrats upped their investments in “free market” think tanks, university programs, right-wing magazines, and other forms of propaganda. Oil shocks, inflation, and European and Japanese industrial revival would soon rattle American dominance. What haunted America was not the misty specter of revolution but the solidifying specter of reaction.