History remembers F. Scott Fitzgerald as the author of The Great Gatsby, but that reputation arrived posthumously. While he was alive, his 1920 debut novel This Side of Paradise was his calling card. Its descriptions of the loosened morals of his generation established the twenty-three-year-old writer as the voice of the Jazz Age, and its publication convinced Zelda Sayre to offer him her hand in marriage.

Fitzgerald took the book’s title from “Tiare Tahiti,” a poem by the late-Victorian writer Rupert Brooke, in which the poet rejects heavenly “paradise” as the folly of the wise, and turns instead to the fleshy pleasures of the Tahitian isle. Likewise, the novel’s Amory Blaine, Fitzgerald’s most transparently autobiographical protagonist, pursues fulfillment in liquor, women, and high society, paradise be damned.

Paradise, though, still has a hold on Amory. Haunted by Catholicism, “the only ghost of a code he had,” he remains torn between the worlds of flesh and spirit. Fitzgerald was really writing about himself. Long after he claimed to have left the church, he described himself as a “spoiled priest,” a divided soul unable to pursue mammon with a clear conscience. Arthur Mizener used the phrase as a motif in The Far Side of Paradise, the first biography of the author, which helped resuscitate Fitzgerald’s reputation and to this day remains the standard for insight into his psyche.

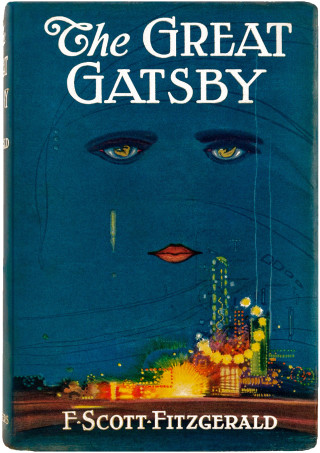

David S. Brown, in naming his new biography Paradise Lost: A Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald, places himself squarely in Mizener’s wake. In the crowded field of Fitzgerald scholarship, the scope of Brown’s book deserves this ambitious title. A historian by trade, Brown argues for Fitzgerald’s status as a cultural critic who charted the decline of America from the high ideals of the nineteenth century to the “soulless materialism” of the twentieth.

This angle provides a fresh look at Fitzgerald’s role in shaping our understanding of the modern age, but Brown’s errors and unsteady grasp of Fitzgerald’s work ensure that the author himself remains hidden.

Brown places the writer in conversation with similar-minded intellectuals of his era, such as the economist Thorstein Veblen and Frederick Jackson Turner, who argued that the closing of the American frontier subsequently shuttered our cultural imagination. This context helps tie Fitzgerald’s tragic vision more closely to the material circumstances of his time, and specifically, to the rise of industrial capitalism and subsequent decay of civic virtue. Brown is right to draw our attention to the author’s unflinching focus on the American dream. Fitzgerald’s father, an ineffectual man born into a fallen Southern lineage, imparted to his son his nostalgia for antebellum aristocratic ideals, but “twentieth-century America’s rising republic of consumers” guaranteed that this bygone era remained a “paradise lost.” Brown argues that Fitzgerald, like Gatsby, was “borne back ceaselessly into the past” in a futile attempt to recover it.