[Editor’s Note: Over the course of 2022 and 2023, New American History Executive Director Ed Ayers is visiting places where significant history happened, and exploring what has happened to that history since. He is focusing on the decades between 1800 and 1860, filing dispatches about the stories being told at sites both famous and forgotten. This is the 20th installment in the series.]

People have heard of “the 49ers,” the tens of thousands of people who rushed to the newly discovered goldfields of California. Men from Mexico, Chile, Australia, China, and elsewhere descended on the Sierra Nevada mountains to the east of Sacramento. These fortune seekers took advantage of the shipping networks of the Pacific Ocean to travel to San Francisco, reaching their destinations far faster than easterners who had to contend with the long overland trails or the expensive route around Florida, across the isthmus of Panama, and up the coast to San Francisco. The California Gold Rush emerged as an instant and enduring part of American folklore, the very embodiment of the sudden riches awaiting intrepid adventurers in the new nation.

In 1859, a Georgia man named John H. Gregory discovered another cache of gold in a gulch on the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains. Back in California, the gold that had first beckoned in creek beds, ready for the taking by anyone patient and lucky enough to sift sand and pebbles at the right place, had given way to expensive gold mining operations that devastated entire mountainsides. The gold discovered in the Rockies, by contrast, shone like that of early California, alluring in shallow streams. By that time, too, the Overland Trails had ushered hundreds of thousands of migrants to the West. Stations, stores, and forts made the journey faster and easier. Telegraph lines stretched all the way to St. Louis from every American city. It seemed that the Colorado gold rush would rival that of a decade before.

Abby and I found ourselves at the site of Gregory’s 1859 discovery by accident. We were traveling from Fort Laramie in Wyoming to another fort in southern Colorado, looking for a mining town near Colorado Springs. Most of the towns we encountered, however, did not meet our journey’s stringent pre-1860 chronological boundary, so we decided to set up camp to see what we might discover at closer range.

Abby found a KOA near Denver at a place called Central City (despite its distance from the much more central-seeming city of Denver). As we drew closer to the site at twilight, we started noticing signs for casinos — something we hadn’t seen anywhere else in Colorado. We found ourselves climbing into the mountains on something called the Central City Parkway, a surprisingly large highway for a relatively uninhabited region. The KOA was filled with the largest and most expensive RV rigs we had ever seen, gleaming Class A buses pulling expensive SUVs.

The next morning, we discovered that we had slept in what had once been The Richest Square Mile on Earth.

Decamping and driving down into Central City proper, we found the site of the great Colorado gold rush of 1859. The town was striking, juxtaposing shiny new casinos with buildings quite clearly from the 19th century, with few signs of the decades in between.

We headed for the local historical society to get our bearings, happy to discover a museum in an old school at the top of a hill.

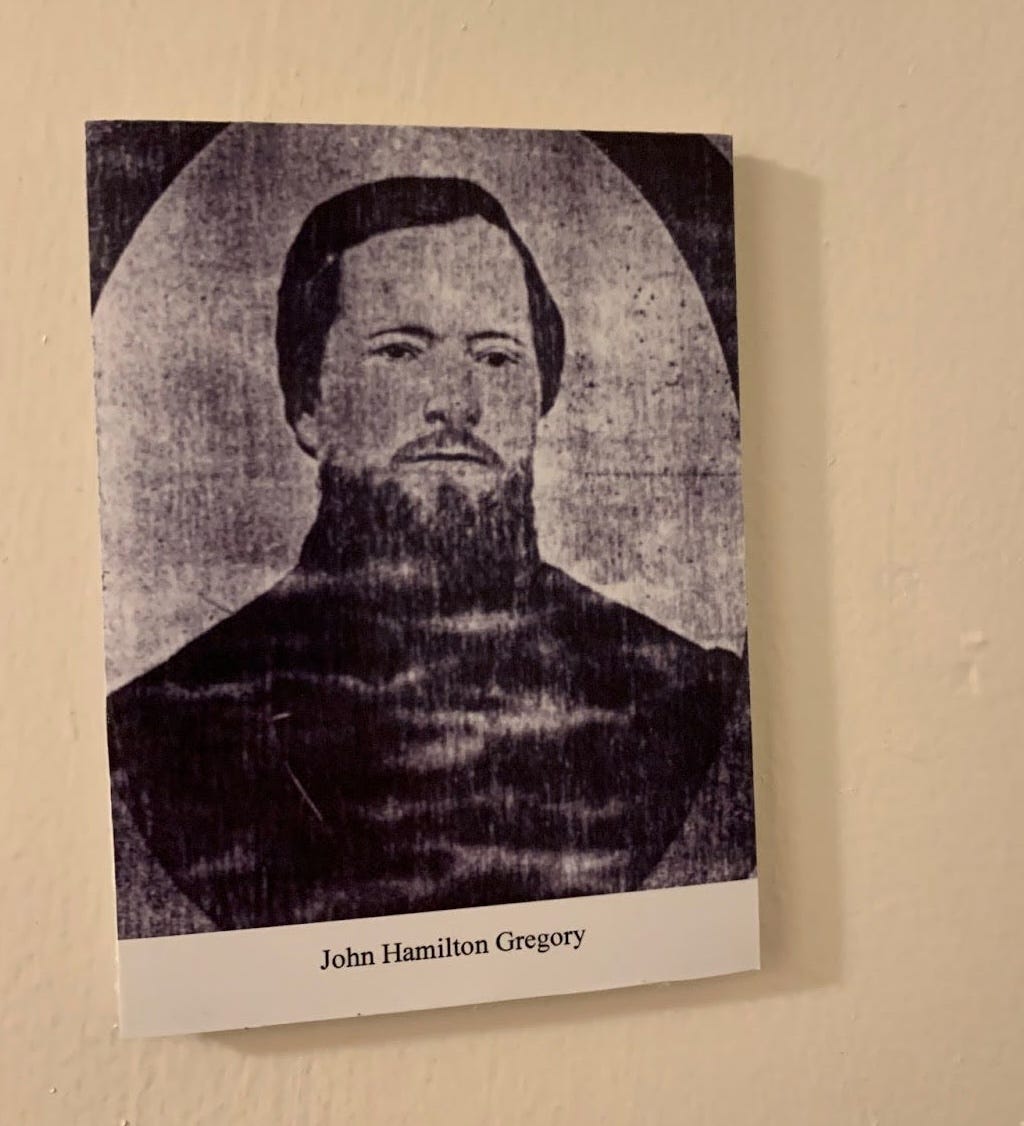

There, a kind gentleman was at first disappointed to hear that I was only interested in the very earliest days of Central City, for the museum was filled with items from other eras, from 1890s-era corsets to class photos from the 1930s. The city had burned to the ground and been rebuilt in 1874, it turned out, so evidence from the 1850s was scarce. Somewhat sheepishly, he told us that he remembered a photo of the founder of Central City, John H. Gregory, in the restroom. We poked our heads in, and indeed, there he was.

Our host welcomed us to explore the rooms upstairs to see if we might find more about the exciting days of ’59, when the ambitious name of Central City had not yet been bestowed on what was then known, more descriptively if less inspiringly, as the Gregory Diggings.

Abby and I looked into every corner and through every glass case, as if we were panning for gold, and turned up several nuggets. We found descriptions of the town’s earliest churches, which arose in “billiard halls, saloons, dance halls, and theaters,” giving a sense of the priorities of the miners. We learned more of the story of Gregory, whose image was not restricted to the restroom. Gregory had been a landowner and gold miner in Georgia. He had set out for British Columbia to find more gold, but while stopping at Fort Laramie, heard promising news from the Rockies. He explored a likely area and, hacking through ice and snow in May 1859, found what he was looking for. He staked his claim, the museum told us, near “the present day Red Dolly Casino.”

Word quickly spread to Denver, where the Rocky Mountain News reported the discovery. By June, more than 20,000 miners had converged on Gregory Diggings. Gregory went back to Georgia and returned several times before disappearing from history, perhaps accounting for his relegation to the museum restroom.

An exhibit with a replica of a miner’s tent demonstrated the way that prospectors lived in the early days of the Gulch. It depicted their canned food and kerosene lanterns, which allowed the men to move to more promising sites at a moment’s notice or to abandon the Diggings altogether.

The “earliest known photograph” of what would become Central City showed a few rough buildings huddling among boulders, perched on the steep mountainside, as the exhibit proclaimed, “seeming to defy gravity in the way they clung to the canyon walls.”

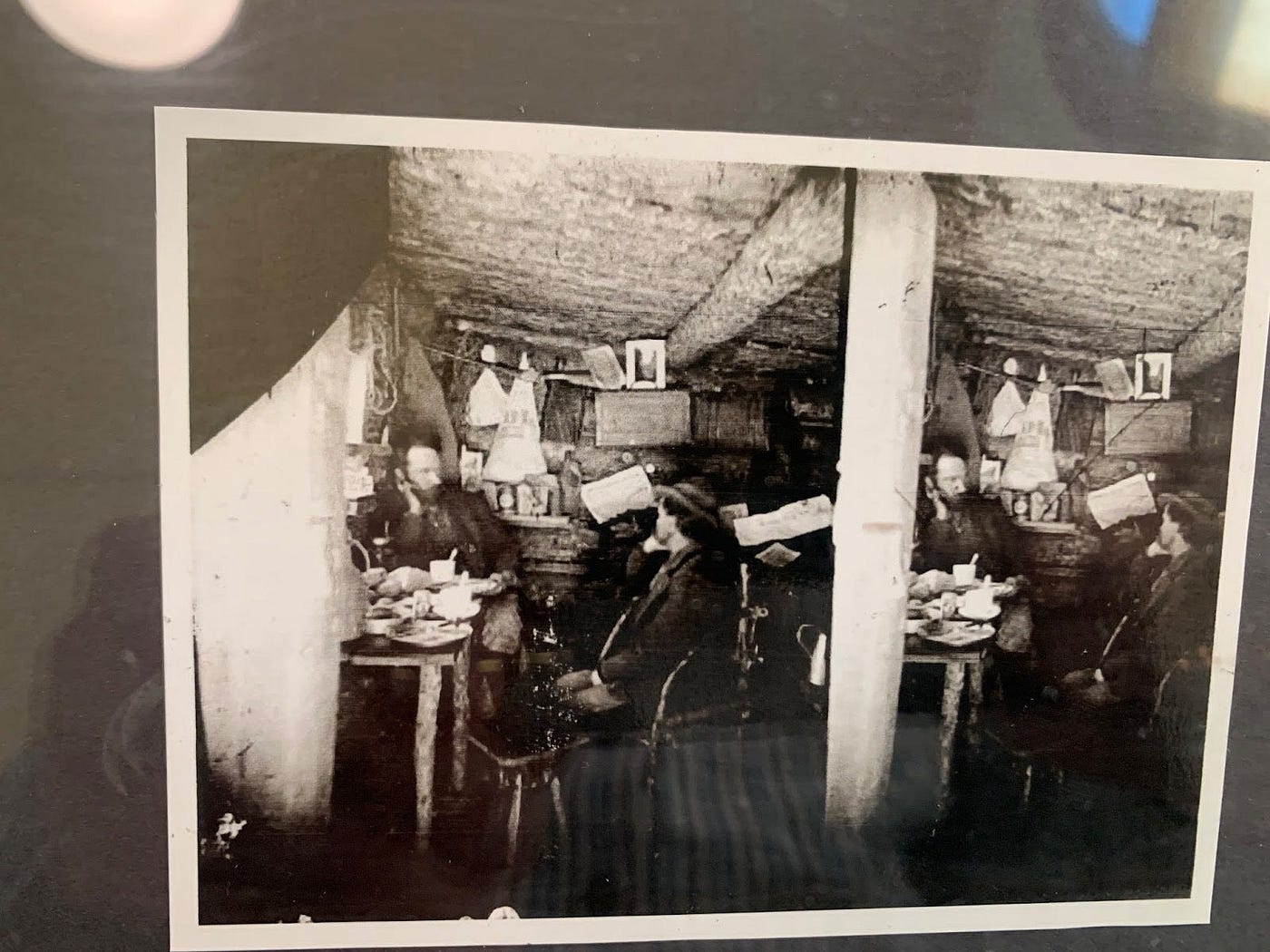

Another photo captured the ramshackle buildings’ dark and cluttered interiors. Its caption explained that “filth and squalor were everywhere as sanitation and beautification took a back seat to the search for gold.”

Central City flourished for generations to come, but prosperity declined across the 20th century as the region’s mineral wealth became ever harder and more expensive to extract. The volunteer at the museum told us something of what had happened to Central City in recent years. In the late 1980s, with its population and economy in decline, the city and its neighbor, Black Hawk– rival mining towns since the first discoveries– applied for and won the right to host casinos. In his telling, Black Hawk had been more liberal in its policies with the casinos and had prospered, while Central City had been more restrained and fallen behind. The parkway we had ridden in on the night before had been built, in fact, in a latch-ditch effort to bring travelers from the interstate directly to Central City, bypassing Black Hawk altogether.

Though our entire trip was something of a gamble, betting that each stop would reveal something significant, Abby and I are not much for games of chance. We were not tempted to try any of Black Hawk’s gleaming casinos, but we were grateful for the chance to see Central City, for a moment the richest square mile on earth.