[Editor’s Note: Over the course of 2022 and 2023, New American History Executive Director Ed Ayers is visiting places where significant history happened, and exploring what has happened to that history since. He is focusing on the decades between 1800 and 1860, filing dispatches about the stories being told at sites both famous and forgotten. This is the 21st installment in the series.]

Everywhere in Texas, the Lone Star flag waves. It dates from almost two centuries ago, but the spirit with which it is brandished feels as alive as it’s ever been. Symbols of American and Texas patriotism join together on everything from public buildings to bumper stickers to T-shirts.

A historian cannot help but notice the strategic elisions and contradictions in the ubiquitous imagery of Texas’ past. The Alamo, a tourist draw in the charming city of San Antonio, embodies the challenges of telling the story of Texas, the United States, and Mexico. Americans often remember that the Alamo, an abandoned Spanish mission, was the site of a desperate battle between a large, elaborately uniformed Mexican army and a ragtag group of Texans fighting for independence from the Mexican government. Many remember, too, that the Mexicans killed or executed all the male soldiers. Beyond those facts, the story can get a little hazy for those who may not have reason to recall that the battle took place in 1836, or that it was followed months later by a victory of Texas forces over the Mexican army.

Many do not know that the curved pediment of the Alamo, which stands as a universal symbol of the Texas Revolution, was a later addition. And it can be hard to remember that Davy Crockett, celebrated as the embodiment of Texas bravery and independence, lived in Texas only long enough to be killed at the Alamo. His line as he left Tennessee after being defeated at the polls is too good to leave off gift-shop merchandise: “You all may go to hell, and I’ll go to Texas!”

The Alamo has recently added the world’s largest collection of Alamo artifacts to its displays. The collection came from an unlikely source: Phil Collins, the unlikely 1980s rock star famous for such hits as “In the Air Tonight,” and for innovating the distinctive gated reverb drum sound that became a ubiquitous sonic marker of the decade. He is one of only three musicians ever to have sold over 100 million records as both a solo artist and band member.

Collins used some of his enormous royalties to fulfill a boyhood fascination with Davy Crockett and the Alamo. In 2014, Collins donated his vast collection of artifacts to the Alamo, where they now fill a new gallery. Collins narrates the story of the Alamo over a large model of the site, where red lights gently illuminate the areas of attack, telling the story of the Alamo as a military struggle of assaults and defenses, of feints and failures.

The Collins addition amplifies the traditional story of the Alamo, emphasizing larger-than-life personalities, physical courage, and bravery in the face of impossible odds. Glass cases display swords, knives, spurs, and projectiles in impressive quantities.

In the new installation, and throughout the museum, a tone of reverence for the fallen martyrs of Texas independence fills the air. Despite the death and execution of the men who fought for Texas independence, visitors, even from far away, cannot help but know that, somehow, Texas triumphed in the war that followed, that somehow and somewhere the arrogant and brutal Santa Anna received his comeuppance. The interpretations offered in the film, statues, and other exhibits lie in unsteady tension between defeat and triumph, between violent death and vindication.

A visitor to the Alamo today would come away with little understanding of the larger struggles that made the Alamo important in the first place. The complicated history of Mexico is reduced to Santa Anna’s ostentatiously uniformed army. The Comanches that rode across the thinly settled landscape seldom appear. Instead, the Alamo is reduced to an isolated struggle, its drama unfolding on a space like a stage set. In this version, the doomed losers were not the victims of misplaced strategies and poor decisions, but rather of overwhelming odds.

An enslaved man named “Joe” figures in the story because the Mexicans spared him, along with women and children, to tell others about the Mexican victory at the Alamo. What is not explained at the museum is slavery’s larger role in the conflict. In the exhibits and film, the Mexicans embody centralized government and its lust for power, while the defenders of the Alamo embody manly courage and local rights. The Mexican abolition of slavery is not featured in the story, and neither is the determination of Texans to expand the system of racial slavery white American settlers had brought with them into the places they dominated.

The Alamo will soon tell a somewhat fuller story. The $400 million Alamo Plan is working with historians and consultants to “tell the full 300-year history of the Alamo,” including “Indigenous Native American groups, Spanish Colonial Settlement, Independence and Revolution, the Battle of the Alamo and its strategic significance, how the Alamo was preserved from ruin to memorial, and the San Antonio Civil Rights movement.” The state estimates that the new museum will “create $12 billion in economic benefits, over 8,100 jobs, and more than $600 million in tax revenues.” But nothing in the announcement indicates that the new interpretation will delve into the role that Texas independence and statehood played in the rapid expansion of Black slavery across a vast area. Nor does it say that Mexico’s abolition of slavery will receive any more attention than it currently does.

About a month and a half after the Texan defeat at the Alamo, the fight for Texan independence continued 250 miles to the east, at the Battle of San Jacinto. There, the Texan Army, under the command of Sam Houston, turned to fight the forces of General Antonio López de Santa Anna. In a mere 18 minutes, the Texians, as they called themselves, defeated Santa Anna’s larger force and captured the general himself, who was forced to sign a treaty recognizing the Republic of Texas. The sacrifice of the Alamo was redeemed with the resurrection of San Jacinto.

The battlefield at San Jacinto (pronounced by white Texans with a hard “j”) is now a part of Houston, the fourth largest city in the nation. The view from its stone tower, erected in the 1930s, overlooks a busy scene of ships and storage tanks as well as a reflecting pool. The many words inscribed around the friezes at the base of the large structure declare the battle to be one of the most consequential in history, and in many ways it proved to be. The United States bears its current shape largely because of the millions of square miles taken from Mexico in the war that followed the addition of Texas as a state.

The museum inside the tower documents the interpretive changes at the site. Older exhibits, rich in artifacts, tell the story of Texas independence much as it is told at the Alamo, as a military struggle of white men determined to be free of tyrannical government. Exhibits installed in the last few years tell a fuller story.

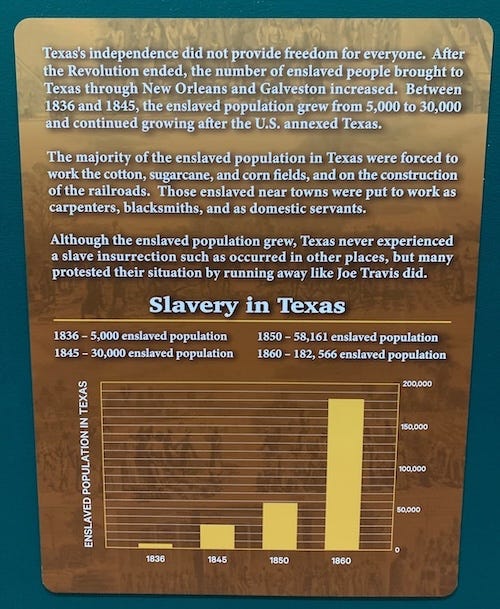

One graph in particular reveals a profound consequence of the war. It shows that in 1836, 5,000 people were enslaved in Texas. That number grew to 30,000 in the new Republic of Texas. After Texas entered the Union in 1846, slavery grew even more rapidly, to encompass 58,000 people in 1850 and 183,000 in 1860. The addition of this information marks a significant shift in historical interpretation.

Texas historical sites must also contend with the reality that 40 percent of the Texas population is made up of people of Mexican descent. That proportion is about the same as the white, non-Hispanic population of the state. Telling the story of Texas’ independence from Mexico — a war in which Tejanos (Texans of Mexican ancestry) played a leading role — complicates a story that has too often been simplified into a narrative of white Anglo-Saxons rejecting tyranny by a distant government, a narrative that maps easily onto current-day politics.

The impressive new Witte Museum in San Antonio places cultural interaction at the center of the stories it tells. One large display traces the history of Pecos Valley inhabitants thousands of years before European contact, presenting a fascinating exploration of their lives and the rock art they left behind. Visitors learn that the Indigenous populations of northern Mexico were much on the minds of both Mexican and Anglo settlers, for the Comanches and Apache launched raids on farmsteads regardless of the language the settlers spoke. A statue of a young mounted Comanche warrior conveys a sense of the power and speed with which they moved across the vast landscape.

The Witte Museum’s “Cultural Mix Theater” weaves together images and music to dramatize the creation of Texas culture from many sources. Here, Davy Crockett appears not as a soldier but as a fiddler, without the coonskin cap that he never actually wore. Native, Mexican, and European cultures appear on large screens, influencing one another in rich combinations. The theme of cultural interaction appears throughout the museum, a large part of which is built around a recreated town square, where people of Mexican ancestry welcome visitors into 19th-century homes and shops that stand alongside those of German immigrants and migrants from the United States.

Texas was not the only place, of course, where peoples and cultures mixed and clashed throughout the vast borderlands of the American West. Abby and I had stopped in southeastern Colorado on our way to Texas to visit an important outpost on the Santa Fe Trail. What we saw there seemed even more impressive, its story even more important, after visiting the Alamo. Established in 1821, the Santa Fe Trail connected Missouri with Mexico and enabled flourishing trade between the two nations.

Bent’s Old Fort offers a dramatic recreation of a place where diverse groups of people met for purposes of trade. The “old” refers not to the age of the 1833 fort, but rather to the presence of a “new” fort that Bent built after he burned the first one to the ground in 1849, following a cholera outbreak. Bent’s first fort, predating and outliving the Republic of Texas, reflected the comity and mutual benefit in the borderlands. According to the National Park Service website,

Bent’s Old Fort was an important point of commercial, social, military, and cultural contact between Anglo-American, Native American, Hispanic, and other groups on the border of United States Territory. The fort served as a point of exchange for trappers from the southern Rocky Mountains, travelers from Missouri and the east, Hispanic traders from Mexico, and Native Americans, primarily from the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, and Kiowa Tribes.

The building was never fired upon nor involved in violent conflict among people now often portrayed as inevitable enemies.

The rooms in the reconstructed fort, designed in line with the historical and archeological record, demonstrate the remarkable range of trade in the region. Some contain goods from China and Europe that were exchanged for beaver and deer skins from hundreds of miles away. Another holds a large billiard table, while others depict men in elaborate Native dress gathered with men in Anglo style, and recount stories of fandangos where everybody danced with one another. Some rooms are decorated with Mexican paintings and religious items, while others depict Native men smoking pipes of tobacco brought from far away.

Bent’s Old Fort and the Witte Museum tell a story that’s quite different from the stories being told at the Alamo and San Jacinto. It’s a story of cooperation and coexistence, rather than of conflict. These stories acknowledge that people of Anglo and Mexican backgrounds have lived together, and shaped one another, far more than they have warred. They recognize that Native people had histories far longer and more complex than the bit parts they play in depictions of warfare against white settlers.

Americans have long thought of the West as “the frontier,” an ever-expanding boundary between the civilized, commercial, and democratic United States and a chaos beyond. Places such as Bent’s Old Fort and the Witte Museum, however, reveal borderlands where boundaries shifted and crossed, where identities changed with circumstance. Such sites offer a rich vision of a vast landscape whose possibilities continue to unfold.