[Editor’s Note: Over the course of 2022 and 2023, New American History Executive Director Ed Ayers is visiting places where significant history happened, and exploring what has happened to that history since. He is focusing on the decades between 1800 and 1860, filing dispatches about the stories being told at sites both famous and forgotten. This is the 18th installment in the series.]

Edgar Allan Poe lived at 35 different addresses in his 40 years. The orphaned son of itinerant actors, he never truly belonged anywhere. Taken in but not adopted by foster parents in Richmond, Poe lived in England, Charlottesville, Old Point Comfort, Sullivan’s Island, West Point, and then Baltimore, Richmond again, Philadelphia, New York City, Richmond again, and then finally in Baltimore, where he died on his way to New York. He searched for ways to make a living with his pen and to protect the health of his fragile young wife, purposes often at odds with one another.

While other famous American authors embodied a particular place — Thoreau is synonymous with Walden and Whitman with New York — Poe seemed to be from everywhere and nowhere. His fiction and poetry barely referred to any place in America, evoking instead places in the Old World and fevered imaginations. And yet Poe is often credited with being the most influential American author around the world and across the generations. If he did not actually invent the detective story or the psychological tale of horror, he stamped those genres with his distinctive voice.

A search for places associated with Poe leads into parts of cities tourists do not usually go. Poe, his wife, and his mother-in-law lived where they could afford the rent, at least for a while. Those places were cramped, pushed to the margins of cities. Most of them have long been demolished. Those that survive tell eloquent stories. As different as they are, each place the Poe family lived elicits the same feelings: astonishment that Poe could write the things he did in such circumstances, puzzlement that he could not translate his talent and ambition into even a modicum of security, frustration that he seemed to be his own worst adversary, gratitude that people held on to the fragments and ruins he left behind, and sadness, if not surprise, at the many ways his legacy is trivialized, marketed, and parodied.

For generations, people have preserved pieces and places of Poe, to tell his story to new generations, and to attempt to understand what Poe was thinking. The landscape of memory has been continually moved, lost, found, rediscovered, reinterpreted. It is not possible to see Poe in just one place, for he merely alighted for a moment. Excellent books have been written about those places — J. W. Ocker’s Poe-Land, Scott Peeples’ The Man of the Crowd, and Christopher Semtner’s Edgar Allan Poe’s Richmond — and they illuminate and connect the sites. Over the past few months, as Abby and I have made our way up and down the eastern seaboard on our public history road trip, we have visited many of those places, discovering along the way that Poe’s life bore its own distinct geography.

Poe’s legacy has led to the preservation of places that would not have been saved otherwise: a tiny rental unit in Baltimore, a lean-to addition in Philadelphia, a rickety farmhouse in the Bronx, pieces of furniture, clothing, and glassware in Richmond. To trace Poe is to trace the lives of many Americans of the era, people who lived precarious lives in places not built to last, and who moved repeatedly in search of stability.

Perhaps it is fitting to begin Poe’s story with a gravesite, for the 1811 death of Poe’s mother in Richmond shaped everything else in his life. Elizabeth Poe was a young, beautiful, and talented actress. She married at 15, was widowed at 19, and then bore three children with her new husband in her early 20s. That husband, also an actor but less talented than his wife, abandoned the family and disappeared. Elizabeth, on tour despite obvious illness, dying of tuberculosis in Richmond, pleaded with friends to take in her children.

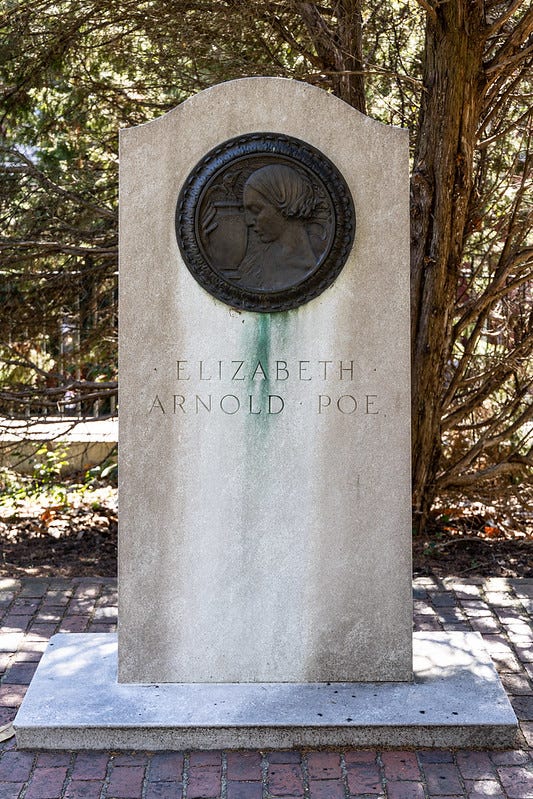

Elizabeth Poe was buried in an unmarked grave at St. John’s Church in Richmond. In the early 20th century, admirers of Poe erected a memorial near the place they assumed she had been interred. A bronze plaque bears Poe’s proud proclamation that he was “the son of an actress” who consecrated to drama “her brief career of genius and of beauty.” Poe visited his mother’s grave often in his youth, and for the rest of his life, worshiped frail young women who died too young.

Despite this loss, Poe was not a morbid young man; indeed, he prided himself on his athleticism, strength, and popularity as he came of age in Richmond. He attended the University of Virginia in 1826, in the brief period when Thomas Jefferson still lived to see his creation taking form. It is possible that Poe met Jefferson or attended his funeral, a strange juxtaposition of centuries and temperaments.

In his time at UVa, Poe was provided with insufficient living funds by his foster father, and famously fell into debt as he gambled to secure money to support himself. He left the university after a brief time, under a cloud of rumor. Generations later, faculty and students honored Poe by founding the prestigious Raven Society, still active today. The university preserves a room in the quarters where he lived, its meager furnishings visible through a plexiglass door.

Poe joined the Army after he left the University of Virginia. Contrary to stereotype, he was an excellent soldier and rose through the ranks at Fort Monroe, Virginia, and on Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina. He was then admitted to West Point, where he again did well until he chose not to, neglecting classes and chapel. He moved to Boston and published a book of poems funded by his former classmates at the military academy.

With uncertain prospects, Poe moved to Baltimore to live with his paternal grandmother, aunt, and cousins. Cholera drove the family to a duplex on the outskirts of town, a tiny house of 600 square feet that has been preserved in a neighborhood that has undergone many changes since. There, Poe wrote one of his first stories, the disturbing tale of Berenice. It was there, too, that Poe fell in love with his young cousin, Virginia, who he married when she was 13 years old. For the rest of their lives, Poe, Virginia, and her mother (who was also Poe’s aunt) would live together in one place after another.

Poe and Virginia returned to Richmond, where he served as an editor at the Southern Literary Messenger and became well known for his brutal reviews of poetry and fiction. Despite his growing national profile, Poe was fired from the magazine. He moved his small family to Philadelphia, where they rented a place on the edge of the city. It was in that home, a sort of lean-to against a larger brick house, that Poe composed some of his most powerful stories.

More than any other home associated with Poe, the Philadelphia site, operated by the National Park Service, bears signs of interpretation. Life-sized paintings create a sense of what the home might have looked like when the family lived there. In the basement, where actual cobwebs lend an air of authenticity, a stuffed black cat sits menacingly near a brick wall where young visitors might imagine a cat — or a person — entombed alive.

The playful tone at the site continues into the exhibits at the interpretation center, where visitors can hear a spooky recitation of “The Raven” through a tube and choose from an array of Poe-themed T-shirts, stuffed animals, and knickknacks. Visitors can also see a room furnished as Poe described the ideal place to read, the sort of room he and his family could never hope to inhabit. It is the most haunting space in the house.

Poe, Virginia, and his mother-in-law left Philadelphia for New York City in 1844 to escape rumors of drunkenness and, they hoped, to find opportunities. Poe achieved his greatest fame in New York when he published “The Raven” in 1845, to universal acclaim and the honor of widespread parody. With Virginia’s health continuing to decline, however, the family moved again, in hopes that the fresh air of the countryside would help. They found a farm located far from Manhattan in a rural area later known as the Bronx.

Remarkably, the farmhouse has been preserved over the generations even as apartments, businesses, and highways grew up around it. It was moved out of the way of development early in the 20th century and has remained at the center of a small park ever since, surrounded by busy streets, apartment houses, and businesses. The bucolic New York Botanical Garden sits less than a mile away, its pristine paths, imposing trees, and exotic specimens an immeasurable distance in tone from the site of Poe’s house and the neighborhoods that surround it.

On the farm, the Poe family found the greatest peace they would ever know, even as Virginia’s small body was wracked with bloody coughing. She grew ever more pale, lying in a tiny windowless room, covered with Poe’s West Point tunic for warmth. The house still contains two poignant pieces from the time the couple lived there: a small mirror, where one can imagine Poe and Virginia seeing their reflections, and the bed where Virginia lay until she died. She was buried on the farm.

As Poe mourned Virginia, he wrote what he considered his greatest work, the “prose poem” Eureka. In that work, Poe explained the essential workings of the Universe, describing how everything exploded from a single particle into the vastness of space. Over time, those elements, he believed, would collapse back into one another, attracted to the point of their origin. Poe delivered one lecture about his vision in New York, to considerable admiration. But the small book confused reviewers and readers, and found no audience in the market.

Poe returned to Richmond, where he hoped to rebuild his life and reunite with a sweetheart from his youth, now herself a widow. He received a warm welcome in his hometown, and it appeared that the young man would be able to regain his balance in the world. He proposed marriage to the woman he hoped would become his wife. He delivered well-received lectures and joined a temperance society.

The Poe Museum in Richmond holds touching reminders of this brief period of happiness. Located near the sites of Poe’s youth, his mother’s grave, the Southern Literary Messenger offices, and the home of the woman he hoped to marry, the museum has for generations gathered artifacts from family, friends, and admirers of Poe. Tens of thousands of people from around the world make pilgrimages to Richmond to see a handwritten manuscript of Poe’s early poem, “To Helen,” his pocket watch, Virginia’s small jewel case, his’s trunk, a ring with his name inscribed inside, and a worn waistcoat with elegant stitching. A bust serves as the object of affection; lipstick marks the poet’s head.

Hopeful of finally fulfilling his dream of editing his own magazine, Poe set out for New York. He never arrived, for he was found in Baltimore, delirious and dressed in clothes not his own. He died of unknown causes and was quickly buried in the city.

Immediately, Poe’s legend arose, first as a result of character assassination. As the decades passed and Poe’s reputation grew, the City of Baltimore moved his remains to a more prominent place and erected an impressive tombstone. Virginia’s remains were excavated from New York and reinterred beside her husband. When her mother died in the same Baltimore hospital where Poe had died, she too was buried at the site.

Today, cities compete to claim Edgar Allan Poe as their own. Baltimore’s professional football team calls itself the Ravens — perhaps because it is a menacing bird that complements the famous baseball Orioles — though the namesake poem was written in New York. Boston, where Poe was born but came to be hated, has erected a striking statue near the Boston Commons, imagining a Poe in triumphant return, accompanied by a flying raven. In Richmond, a statue of a seated Poe sits near the state Capitol building, designed by Thomas Jefferson, within sight of a giant memorial to George Washington and other Founders.

The irony is too obvious for a poet of Poe’s sensibility. A man who could find no home, no security, and no financial stability in America is claimed by cities that showed him no affection or respect while he was alive. Business enterprises profit from his likeness while storytellers steal his plots and mimic his tone. The tragedy of Poe’s life has itself become a commodity, a trademark, a joke. Visits to the places he lived, however, remind us that there was a very real, and very human, person behind the haunted images that refuse to die.

This is the 18th installment in American Journey, a travelogue documenting my visits to public history sites around the country. Read the rest of the series here.