Collection

Revising History

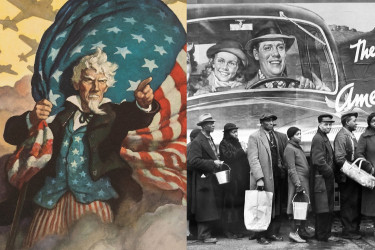

In public discussions about history, the term “revisionism” is often invoked as an accusation, to suggest that a certain interpretation of the past has been made disingenuously, and is not to be believed. But within the discipline, it is often embraced as a description of sound historical practice whereby outmoded understandings of the past are acknowledged and corrected for. This collection gathers stories about the latter version of revisionism, both when it is and isn’t labeled as such.

Two places where the term has recently entered public discourse are in debates about the content of history textbooks and about the 1619 Project. In this article, Michael Harriot looks at the history that critics of the 1619 Project learned in school to better understand the narrative that they believe it to be challenging.

Here, Erin Bartram asks what it means to accuse a historical interpretation of being revisionist, and why historians should embrace the charge. “The questions and doubts that are part of accusations of ‘revisionist history’ are very similar to the questions and doubts that historians express as part of our day-to-day work.”

Even the Founders engaged in revisionist history. The ways they had understood their past as British subjects suddenly seemed inadequate to explaining their present circumstances. To meet the challenges facing the new nation, as Michael Hattem explains here, they needed a story that emphasized unity and independence.

W. E. B. Du Bois's most important contribution to historical scholarship was his re-evaluation of Reconstruction that offered an alternative to the "Dunning School" perspective that dominated historical scholarship at the turn of the century. It took decades for the historical profession to acknowledge that Du Bois's revision improved our understanding of the period; hence this obituary from the American Historical Association that arrived 60 years too late.

Understanding the methodology behind a revisionist history is critical to assessing whether it enhances or obstructs our ability to understand the past. In the 1970s and '80s, conservative Christian leaders crafted a narrative that placed Christianity at the center of the nation's founding. As Lauren Kerby notes, however, “they took the written records of the past at face value with little interrogation of context or the potential that narrators might be unreliable.”

With new interpretations of the past constantly being offered, and old ways of thinking often left unquestioned, T. J. Stiles thinks it would be helpful to bring more attention to the origins of the stories we tell about ourselves. Especially because memory, politics, and academic history are constantly interacting to influence each other and to shape policy and society.

Responding to the 1619 Project's interventions, and to its revisions of its own arguments, historians Leslie Harris and Karin Wulf explain that history is always a process. Asking whether a historical interpretation is right or wrong may not be the most useful question. As with science and medicine, our understanding of history is complex, contradictory, and always changing.

Here, William Hogeland reflects on the mid-20th-century origins of the founding narrative that has pervaded “museum exhibits, trade publishing, broadcasting, op-eds, and political speeches” for decades, even as historical scholarship has moved beyond that simplistic story. Its deep entrenchment in American culture, he argues, helps explain why revision is difficult for many Americans to fathom.

Censorship can be revisionist, too. Whistleblowers at the National Archives have accused the institution’s leadership of bowing to pressure from right-wing politicians to remove certain figures and events from exhibits about westward expansion and the civil rights movement. Nathan Robinson makes the case that it takes vigilance to ensure those in power cannot bury aspects of history they wish to suppress.

Finally, some words of wisdom from Michael Hattem about how history is never final: “First, I want people to realize that the past is subjective, not an objective thing. We turn the past into history by interpreting and attaching meaning to it. Then, I want people to realize that this process of rethinking the past—what the past means—is a fundamental part of our political culture, and has been since the founding of the nation.”