Collection

Historians in Public

History is one those fields that has a broad audience, drawing in many people who aren't academics or students. Bunk is full of history writing for the general public, but this collection gathers writing ABOUT that writing. How have historians succeeded in reaching beyond the academy, how has their work filtered into public consciousness, and how could historians more effectively enter public discourse?

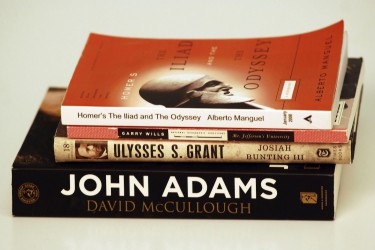

Many see the mid-20th century as a golden age of historians as public intellectuals. A recent book surveys some of the giants of the era, including Richard Hofstadter, Daniel Boorstin, John Hope Franklin, Howard Zinn, and Gerda Lerner. In this review, David Waldstreicher takes stock of the strategies used by these historians to reach a broad audience, and considers what their examples mean for historians entering public discourse today.

Scott Spillman thinks mid-20th century historians like Arthur Schlesinger and C. Vann Woodward became popular because of "their willingness to subject the United States to a critical reexamination at a time of intense pro-American propaganda and political pressure." He sees an heir to that tradition in Matthew Karp, who uses popular writing "to make people more self-conscious about their society, to unearth its underlying values and assumptions and to show how past events" created today's world.

Joshua Rothman, one of the historians quoted here, sees value in social media: “For historians, even writing an op-ed might have a delay of a couple of days. But Twitter allows for the transmission and circulation of historical knowledge and context in real time, as events are unfolding. And even though that speed does lead to less careful consideration than a lot of people might like to see, the news cycle moves so quickly that context sometimes never appears unless it’s provided on the spot.”

During Trump's first term, a host of historians took to Twitter, Substack, cable news shows, and other public forums to employ their expertise to resist politicians' attempts to control public understandings of our society. Charlotte Rosen follows how their use of history as a tool of resistance fell away when they suddenly found that they agreed with those in power.

When one is a successful public intellectual like Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, whose biography, documentary, and website on Martha Ballard have entered the popular consciousness, others begin to use one's work without attribution. Karen Wulf thinks the problem is cultural: When we think about intellectual work as individual creation, it masks the collective labor from which all human knowledge is built. So how should we acknowledge our sources of information and inspiration?

A recent debate about "presentism," and how much current politics should play in history, recently spilled out of academia into the public sphere. Where is the line between framing history in terms of how it helps us understand the present and letting concerns of the present determine the topics of research and the ways interpretations are shaped and presented?

Sometimes the influential historical interpretations come from people with the most reach, rather than the most insight. In the case of billionaire David Rubenstein, his wealth buys him access to public platforms, where the view of history he promotes is one that doesn't challenge, and even actively elides, ethical questions about the negative social impacts of the wealth and corporate power that have offered him this public platform in the first place.

Sometimes historians and their ideas enter the public sphere even when they do not seek to do so. As a graduate student, Greg Ablavsky wrote a doctoral thesis on early America for an academic audience. After Clarence Thomas misinterpreted his conclusions in order to justify a Supreme Court decision, Ablavsky set the record straight.

Two perspectives on what historians can contribute to political analysis. Julian Zelizer thinks "historians are particularly well positioned to place current events in longer time frames and to offer more perspective on the origins of a certain situation," while Morton Keller worries that they risk political bias and oversimplification when they frame their contributions around the latest news.